“I Knew Mads Mikkelsen Could Do the Hitman Part in His Sleep”: Bryan Fuller on His Film Debut Dust Bunny

Ahead of the release of his first feature, the writer and director discusses collaborating with Mikkelsen and Sigourney Weaver, his family-friendly 80s horror influences, and a potential Hannibal revival

by Heather O. Petrocelli 10 December 2025 Extended interview originally published in Issue 004

Courtesy of Roadside Attractions

Bryan Fuller has never been afraid to walk a tonal tightrope. His genre-bending television has redefined storytelling through sumptuous, grimly romantic imagery and unflinching examinations of death, identity, beauty, and queerness. Pushing Daisies was a “forensic fairytale” defined by a campy creepiness. Hannibal blended a brutal police procedural with a devastating queer romance (between a cannibal and an FBI agent). Now, making the jump from TV to film, his latest work is a twisted fable—part-action, part-horror—with an alluringly simple premise: a little girl (Sophie Sloan) hires a hitman to kill the monster under her bed.

Starring Mads Mikkelsen and Sigourney Weaver, Dust Bunny sees Fuller bring his signature visual splendour to the silver screen. In a sprawling conversation with Heather O. Petrocelli, author of Queer for Fear: Horror Film and the Queer Spectator, Fuller breaks down the making of his directorial debut, his relationship with mortality, and what it means to be a queer storyteller during this moment in US history.

Sophie Sloan as Aurora in Dust Bunny. Courtesy of Roadside Attractions

Heather O. Petrocelli: What drew you to Dust Bunny as your first feature film?

Bryan Fuller: It started as an episode for the Amblin show Amazing Stories on Apple [TV+]. There were a lot of stories I loved that I couldn’t get the executives at Apple excited about. This was one of them. After pushing it uphill for so long, I was like, ‘This would make a really good movie.’ The story is simple, on its surface, and would allow me to do some fun things with the camera as a directorial debut. Then I wrote a feature script, and it lived and died and lived and died… For five years, we tried to make it, and finally, someone was like, ‘We want it.’ And I said, ‘Would you make it with Mads Mikkelsen?’ And they said, ‘Yes.’ A lot of studios that I had been dealing with wouldn’t finance it based on that attachment.

HOP: How did you find the transition from TV to film?

BF: It was relatively organic. The show was an anthology, and we wanted each episode to be an Amblin movie. Because that was the highlight of my summer moviegoing experiences in the 80s: these wonderful high-concept gateway horror children-in-peril stories like The Goonies or Poltergeist. I particularly liked the summer of 1984. There were so many high-concept original movies like Ghostbusters and Gremlins and Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, which was a sequel, but you still got somebody pulling a heart out from a guy’s chest and setting it aflame.

“I still am that kid who loves those big, high-concept stories that have an emotional root.”

So there were now all of these horror elements in mainstream summer movies. My head was exploding because I ate these stories up, and they were coming at me with such rapid fire. I had missed that time—and I still am that kid who loves those big, high-concept stories that have an emotional root. That was the kind of movie that I was chasing as an audience member, and now I got an opportunity to chase it as a filmmaker.

HOP: This next question fits perfectly with what you’ve just said. Dust Bunny is an homage to movies that can both traumatise and initiate kids into the horror genre. But for you, horror movies were a safe space growing up. What is a horror film you saw as a child that made you feel both scared and safe at the same time?

Sophie Sloan and Mads Mikkelsen in Dust Bunny. Courtesy of Roadside Attractions

BF: There were so many. A lot of my earliest impressions of horror movies are tonal as opposed to narrative. When I think about films that disturbed me as a child, I go to things like Let’s Scare Jessica to Death, which is not necessarily a great movie, but it was on cable. Cable that we were stealing from our neighbours. My dad was an electrician and climbed the telephone pole and wired it into our house. So when I was watching these movies, I also knew that it was illegal—and that we couldn’t tell people we had cable because the scary people would come to our house. ‘Are they going to take me to jail because my dad stole Showtime?’ So seeing them on cable had an extra kind of percolation.

In Let’s Scare Jessica to Death, what struck me was the paranoia of the story—that you can’t trust anybody around you. It was very relatable because I grew up in a violent house. The scares were the people under my roof, or one person under my roof. Stories about whether or not you are safe with the people you know—they hit my queerness in a very specific way. Movies like The Other, with the twin boys and the pitchfork in the haystack, those crazy little moments that were about paranoia and safety. I was watching movies where people felt that they, too, were unsafe, and as is illustrated in your book, that speaks to us as queer people.

Those films were the ones that unsettled me. But the ones that I loved were Black Christmas, Jaws, Rosemary’s Baby… I saw them early on stolen cable. They were not necessarily unsafe spaces for me because seeing the protagonists survive monsters, demons, and devils gave me an indication that I was going to survive this home environment as well, as a young queer person who was being identified as queer and being forced out of that queerness with a variety of coercive methods.

HOP: You grew up in Idaho, is that correct?

BF: It’s the Lewis-Clark Valley. So it’s Lewiston, Idaho, Clarkston, Washington. It’s one community. And I grew up in a place where my assistant scoutmaster was a serial killer.

HOP: Excuse me… What?!

BF: All of those things were a factor as I was getting obsessed with horror movies. There was a string of murders. I was eight years old when the first body dropped. They went on for like six or seven years, and all of a sudden, I was a background character in a horror movie. I would ride my bicycle out to the bridge where one of the bodies was dumped, and there were still blood stains in the cement. I was keenly aware of feeling unsafe at home. I felt more unsafe in my home than I did in the community with a serial killer assistant scoutmaster, if that makes sense.

Rebecca Henderson and David Dastmalchian in Dust Bunny. Courtesy of Roadside Attractions

HOP: That makes perfect sense. I like how your love of horror had an extra ‘jolt’, from the stolen cable to your assistant scoutmaster serial killer.

Dust Bunny shows a return to the colourful yet macabre world of Pushing Daisies, while adding action into the mix. How did you approach balancing this unique blend of horror, action, and magical realism?

BF: There was something about the absurdity of a little girl hiring a hitman to kill a monster under her bed that required its own reality. Also, what you don’t see in those worlds becomes part of the reality, which I really enjoy as a storyteller. I sit down and think about all the characters and their points of view, and I try to sew together the DNA of a cohesive reality that they can all share. Then I narrow the perspective and keep it to the emotional focus of the story and the protagonist.

HOP: So, based on everything you’ve talked about with your childhood influences, I feel like horror, action, and magical realism just live naturally in you.

“There was something about the absurdity of a little girl hiring a hitman to kill a monster under her bed that required its own reality.”

BF: I think they do. I remember walking out of the first Terminator in 1984—I was 15—and thinking, ‘God, I wish somebody was trying to kill me. My life is so boring in this small town that has a serial killer.’ I still had the audacity to think that the experience was boring. So A) I wished somebody was trying to kill me, and B) I had a thumping Brad Fiedel soundtrack accompanying my pubescence. Those of us from tricky childhoods have a kind of dysmorphic relationship with horror or action thrillers because we’re living in an unsafe situation, yet we are drawn to narratives about people surviving unsafe circumstances. And it’s not necessarily about my survival because my survival is implicit—I’m the protagonist of this story, and Linda Hamilton makes it to the end of the picture. But that’s the pillow. That’s the cosy pillow that we cuddle because when we go home, survival is a question mark. What I love about having this conversation with you is that you’ve written about all of this so beautifully. It’s been your life’s work.

HOP: I could talk horror with you all day. I’m realising how much our experiences overlap: we’re roughly the same age, so everything you reference hits me just as hard. Same emotional imprints, just in different circumstances. I was a welfare kid with a single mom who moved around a lot. That’s probably why I connect so much to the magical realism in your work—it reminds me of Pan’s Labyrinth.

Your stories often grapple with death, but rarely in a grim way. What do you think our cultural narratives get wrong about death, and what are you trying to reframe through your work?

BF: One of the reasons that I am fascinated with death is that it’s the grand equaliser. We’re all driving toward that inevitable cliff. Growing up with a large extended family, I went to funerals of uncles and great uncles and grandparents. There was something about adults making funerals a safe place for a child because they’re trying to limit the stress of those experiences. And I learned about David Cronenberg from my older cousins at funerals talking about Shivers. So funerals were a place where I got to see my cousins, hear about movies I didn’t have access to, and also feel coddled while surrounded by death in a way that allowed me to look at it as an inevitability.

If there’s something I’m trying to do with the exploration of death in my stories, it’s a simultaneous mystification and demystification of it. Looking at Pushing Daisies, the pie maker can bring somebody back to life, but only for a minute. It still commits to the bit of the inevitability of death, and the consequences of avoiding it will always be more death.

My mom died last year, and it was fascinating to see—I’m the youngest of five—the dynamics of everybody’s mourning process. I gave everybody a coupon to grieve how they need to grieve. But what was curious in our political culture was to look at grief through a MAGA lens, because one of my siblings is MAGA and my mom was not—she was relatively anti-Trump and didn’t understand how she raised a daughter to be MAGA. I realised: ‘This is an interesting study of how opposing viewpoints approach grief’—in a way that was reflective of a selfishness, where you believe your grief is greater than everybody else’s, and you demand that it is yours and yours only. It was eye-opening—how we politicise ourselves is a reflection of our relationship with grief.

Sheila Atim in Dust Bunny. Courtesy of Roadside Attractions

HOP: Grief through the prism of politics. That’s fascinating.

BF: It was wild. And I need to write my August: Osage County about it.

HOP: Throughout your incredible career, you’ve worked with some iconic names in film and television. But I imagine that there’s still deep down that little horror kid who thinks, ‘Holy fucking shit, that’s Ellen Ripley.’

BF: Yes!

HOP: What was it like working with Sigourney Weaver on Dust Bunny, both as a storyteller collaborating with a great actor, and on a personal level working with such a horror icon?

BF: It’s still surreal that I got to work with Sigourney. When we were at TIFF, an interviewer asked a not dissimilar question about the iconography of Sigourney’s roles, not the least of which is Ellen Ripley, and what she means to queer kids growing up and what she meant to me as a queer kid. Because the male heroes were not applicable to me.

But why Ellen Ripley, Princess Leia, Wonder Woman, and Geneviève Bujold in Coma were important to me was because the men were an unsafe space in my experience growing up. Straight white men were the most dangerous for me. I’m explaining this to the journalist, how the power of these women was so inspiring, and Sigourney was like, ‘That is so odd to hear because playing that character, I felt powerless. As a woman, I did not feel like I had my power to ensure my own survival, and that’s why it was a battle.’ I was like, ‘You just nailed it! You just nailed why that is so relatable to queer people.’ Because we see ourselves as powerless as well, whether consciously or unconsciously. Women in these narratives, through the lens of society, are less powerful, yet they find power, they persevere, and they survive. That is the most valuable lesson a young queer person can get: you don’t have any power, but you better fucking find it, or you’re gonna have a second set of jaws smashed through your skull. You have no choice.

We know that Ripley is strong. But it was fascinating to hear from the actor about the reality of who the character is—which is somebody terrified about their survival and still surviving. I mean, because we were having the conversation, there were people in the room crying.

HOP: I’d be remiss if I didn’t say that I’ve been looking at a xenomorph in the background of your room this entire time. I say all this after your story because Alien, unsurprisingly, was the #1 favourite horror film of queers in the Queer for Fear survey.

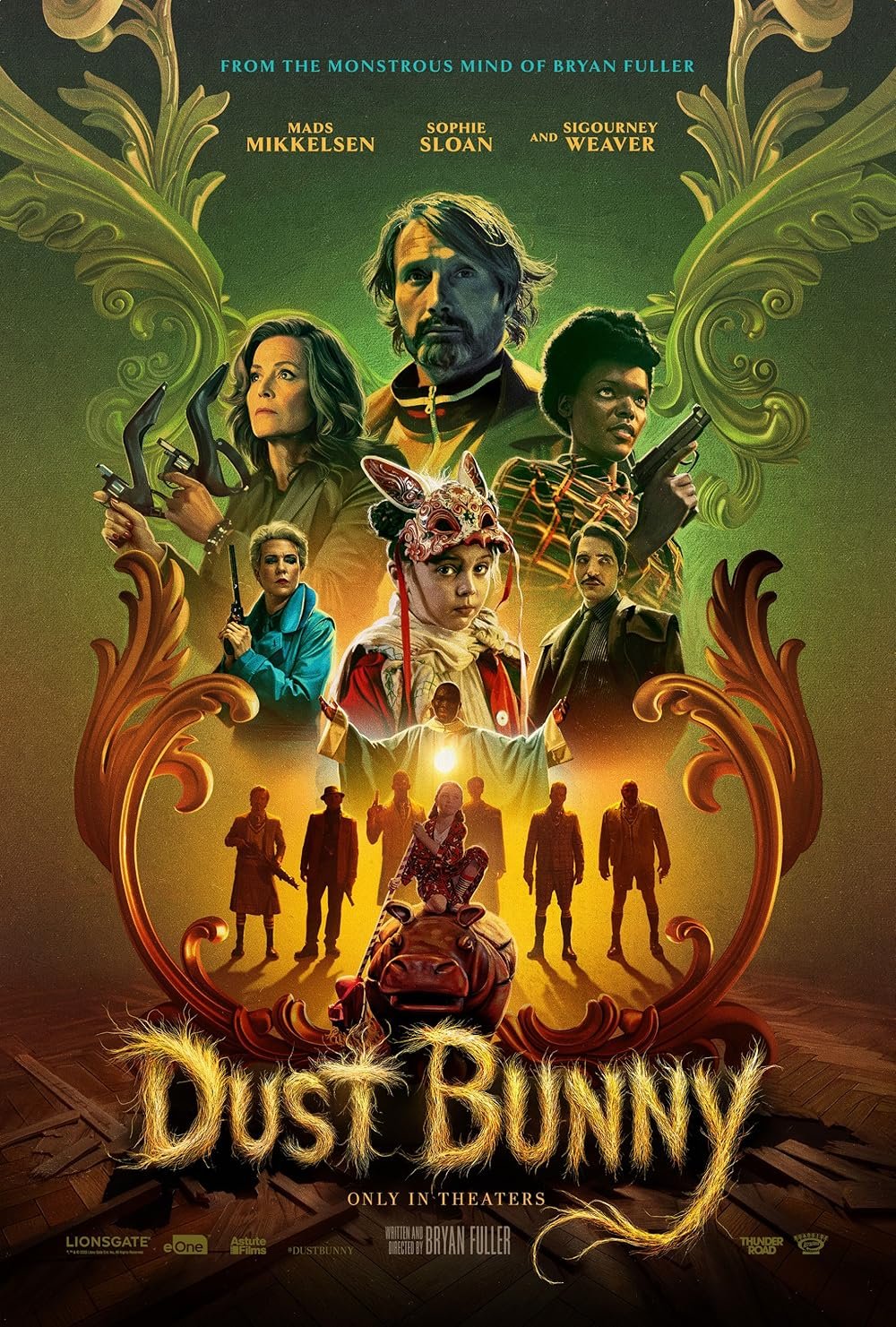

Dust Bunny poster. Courtesy of Roadside Attractions

BF: Yes, there’s something about it. That’s the reason I came to film school—because I was studying to be a psychiatrist. I was taking an experimental psychology course, and my experiment was: do you get more out of a movie if you experience it as a popcorn thriller, or if you have the added levels of Freudian and/or Jungian analysis that gives you greater insight into what the story is? One thing that appealed to me about Alien was that there was a parental figure, a mother, even though in my home, the father was the problem—but the mother was a guardian entity who betrayed her children for a giant cock. I’ve had conversations with Ridley Scott about the design elements, where he suggested, ‘It wasn’t like that—that was H.R. Giger.’ He kind of waved off the deeper psychological implications of the movie, and he was just there to make pretty pictures and tell a surprising story. But the psychology of it is what makes Alien such a profound movie for me as a filmmaker and a filmgoer. It was the first movie where I was like, ‘That production design is saying something.’

There was something about Ellen Ripley, written as a man played by a woman, that has that gender fuckery that makes her so distinctively queer. When I was reading the novelisation by Alan Dean Foster, I think it was for Aliens, when they were talking about Ripley’s daughter, I was like, ‘She doesn't have a fucking daughter! She is a queer woman with her own identity. She’s not married. She doesn’t have kids. She’s just fucking Ripley. And she doesn’t need that to make her a good human to protect this vulnerable child.’ I was glad when I saw the movie that none of that shit was in it, because I was like, ‘Nope, she’s queer. You’re not taking that away from me.’ And I could go on about vagina doors, penis-headed monsters, male rape, forced birth—all of those things that make it kind of this litmus test of how deep your understanding of a movie can go because, at its surface, it’s Jaws in space, but at its soul, it is queer survival.

HOP: Yes, chef’s kiss. You just talked a lot about production design. From shooting in Budapest to collaborating with production designer Jeremy Reed, how did you approach creating the surreal world of Dust Bunny?

“It’s candy-coloured and candy-coated, so you want to lean in and take a bite and taste the sweetness of the world.”

BF: You know what was interesting about filming in Budapest is that, at the time, a couple of years ago, it was a very homophobic, very racist dictatorship. And, well, we’re there as the United States. But one of the things that I loved about working there is we had an amazing location scout who found us these wonderful buildings that had been recently refurbished—like the Hungarian Treasury, which was the apartment building. And that was a tent pole for our aesthetic in many ways. Jeremy and I had a lot of ideas going in about what the film should be, and we talked about the films of Jean-Pierre Jeunet and Marc Caro and their collaborations —Delicatessen, City of Lost Children, and Amélie—wanting this to feel Parisian in its opulence as a fairy tale and a little bit like the witch’s cabin in the forest. It’s candy-coloured and candy-coated, so you want to lean in and take a bite and taste the sweetness of the world.

One of the cool things was going to these amazing fashion houses in Paris where all of Sigourney’s costumes were being built. So when we went to Paris for Sigourney’s fitting with Catherine Leterrier, an amazing and iconic costume designer in France (and mother of filmmaker Louis Leterrier), we also went wallpaper shopping. I love wallpaper. I love patterns and design. A lot of the conversation was creating the jewel box of this fairy tale, but trying not to do so much that it takes over from Sophie Sloan’s [who plays the lead, Aurora] face, which is the real visual effect of the movie—just her expressive face.

Sophie Sloan in Dust Bunny. Courtesy of Roadside Attractions

We didn’t have a ton of resources. I mean, we weren’t a cheap movie—we were under $20 million. But we also had a monster and a child that we could only work six hours a day with, who was in practically every scene of the movie. So a lot of it was having dedicated people stepping up to the challenges. Our props people in Budapest were fantastic. Our grip, the electric departments, and our gaffer were amazing. One of our camera crew, Ferenc—every morning, because we only had a crane for two days of the 40-day shoot—he was like, ‘How long do you want the crane today?’ And we're like, ‘60 feet.’ And he would start strapping scaffolding together with belts and build a crane every morning from scratch because we had that level of dedication.

So much of the movie is about wounded children. One of my closest friends that I came out of the experience with was Olivier Bériot, who was our costume designer for everybody but Sigourney. Catherine’s retired, but she’s been working with Sigourney since Gorillas in the Mist, so she said, ‘I’ll do Sigourney’s outfits, and then Olivier will do the rest.’ It was a great collaboration. Olivier, when he first arrived in Budapest, was like, ‘Can we have lunch because I want to talk to you about the script and whether you are Aurora, the little girl, or the neighbour.’ And I said, ‘I’m always going to be the little girl.’

There’s a line in the movie that was taken from my childhood. When they ask Aurora about her parents, she says, ‘They weren’t very nice to me.’ And that’s all you get about this child’s history. So the audience can either think they weren’t very nice to her because they didn’t give her cha-cha heels at Christmas, or something worse. It’s up to the audience to decide how they see themselves in this character. So Olivier asked, ‘Who are you?’ and I was like, ‘Well, who are you?’ and he said, ‘I am also the little girl.’ He told me the story of his childhood—that was much more extreme than mine, and mine was fucked up—and I saw the value of people being able to have that conversation after this movie. That’s the thing I hope people can come away with—having a fun moviegoing experience that’s first and foremost a romp, but you can scratch beneath the surface. You can ask bigger questions about your relationship with your childhood home, and how that may have left lingering resentments that you still carry into adulthood. But it is a fairy tale. It is meant for children, but it is also rated R. So don’t ask me to babysit your kids.

HOP: I love that you invite us to project our own stories onto Aurora’s—whether we had a childhood like Dawn Davenport or something far worse.

You’ve described Resident 5B as a hitman with a heart, and said no one but Mads Mikkelsen could play him. What did Mikkelsen bring to the role, and how has your creative relationship evolved since Hannibal?

Mads Mikkelsen in Dust Bunny. Courtesy of Roadside Attractions

BF: I knew Mads could do the hitman part in his sleep. What was more appealing for me, knowing Mads as a human being and sitting with him on weekends while working on Hannibal, is that he really is a professional. I had pitched him this idea when it was going to be an Amazing Stories episode at the premiere of Rogue One years ago, and he was like, ‘Sounds great. I’m in.’ When I met him for the first time, I was like, ‘Oh, he’s a movie star.’ I’ve met a lot of celebrities who don’t have the rizz, as it were, in person. And he has more charisma in person than on screen. I wanted to see more of Mads in the performance because he exudes so much more charisma as Mads Mikkelsen than he does as Le Chiffre or Hannibal. When I shook his hand, I was like, ‘He’s a rockstar.’ He’s sort of like the Danish George Clooney.

What I didn’t realise, because I was so busy thinking how cool he was, was that he also thought I was… not necessarily cool, but worthy of his friendship in a way. There was something about this kid from the Lewis Clark Valley talking to this charismatic movie star and then realising, after doing a show with him and then starting Dust Bunny, that we were friends. Even more than friends—we’re fraternal in many ways. And he always had my back. It was a challenging production, and he stepped up at every turn. There was a certain point where Mads just commandeered the stunt team because he had more stunt experience than anybody else on the movie and knew how to do these things. So we would spend Sunday afternoons choreographing fight sequences with Bruce Lee action figures and mock-ups of the sets, and then filming them and sending them to the stunt team. At every step, he was additive. He would pitch things, I would pitch things, we would play in a way that I was like, ‘He’s my friend. This isn’t just a co-worker.’ I guess the long and short of it is I realised that this guy, whom I’m so impressed with as an actor, was my friend first.

“I wanted to see more of Mads in the performance because he exudes so much more charisma as Mads Mikkelsen than he does as Le Chiffre or Hannibal.”

HOP: So it sounds like you, as his friend, wanted to capture more of Mads for this role. To have more of who he is shine through this work.

BF: Yes. I still want to see Mads because he’s still playing the hitman, and there are moments where he’s so charming with Sigourney. What I loved about them working together is that they both had little crushes on each other. There was this kind of school dynamic where they’re both professionals, so they can’t like fan out on each other. But we’d do a rehearsal and Mads would go to makeup, and then Sigourney would, very gentlewomanly, say, ‘I am very enamoured with our leading man.’ And I was like, ‘Yes, he’s very charming.’ And when Sigourney got up, Mads would express equal yet more—because we have that fraternal relationship—direct expressions of his smittenness with Sigourney that are probably not suitable for print. But that was so cute to see where I was like, ‘Do you want me to pass her a note?’ That dynamic was mutual. I told Sigourney about it, and she blushed and said, ‘Well, you just made my day.’ It wasn’t something I shared while we were filming, but afterwards I was like, ‘That was a real mutual appreciation.’

HOP: This story has made my day. At a time when queerbaiting was rampant, you openly acknowledged the love story between Will and Hannibal. Why was it important for you to canonise that relationship, and are you interested in depicting their romance more explicitly in a potential continuation of the story?

Mads Mikkelsen in Dust Bunny. Courtesy of Roadside Attractions

BF: When I set out to do Hannibal, I wanted to tell a story about heterosexual men who fell in love with each other. And then it became a pansexual in love with perhaps a bi-curious man, and then it became something that was totally queer and about falling in love with the other person as a person first and seeing genitals second, which is something that I’m fascinated by as a cisgender man. I mean, I’m a Kinsey Six, so I’m queer and g-g-g-gay, and so there was something about my own restricted perceptions of my sexuality as a cis six that was eye-opening as well.

I feel like their love and their sexuality in many ways are not gendered because they’re in love with each other. I don’t mean it to be a cop-out or queerbaiting, because I do actually feel like the characters earned their attraction to each other. It didn’t start with that intention, but the attraction was coming through so clearly, and it had to be acknowledged. It just reached a point where we had to either acknowledge or deny it. Denying it felt dishonest; acknowledging it felt like a continuation of their arc. It does feel like an arc interrupted in so many ways, because, as somebody who is… There have been opportunities where I have friends who are couples who have suggested dalliances, and I was like, ‘I’m gay.’ I wish I were bisexual because there are so many things that I find attractive about women, but I’m just a big fag.

“I do think the story [in Hannibal Season 4] would go to a place where there would be physical intimacy between these two men.”

So the length of time it took me to get to that place with the characters was probably because I was finding ways to erode my own parameters of sexual expression. Because I see so much of myself in Will Graham, warts and all. So I was like, ‘Is this guy more fluid than I am?’ And the answer is yes. And Hannibal, in my mind, is as fluid as they come. Beauty is the only determining factor of his attraction. Are you beautiful on the inside? Are you beautiful on the outside? Are you capable of beauty and kindness? That is attractive to him.

As a gay man, there’s so much emphasis on aesthetics and our bodies and how we perceive the world through a version of manhood. I think queer men get sucked into a lot of bullshit with the performance of masculinity that is, just plain speaking, boring. So there was something about these men being attracted to each other’s souls and minds. The fact that we had not yet got to any sort of sexual act… that makes it even hotter for me. But I do think the story would go to a place where there would be physical intimacy between these two men. I hope that we get to tell that story. I think the rights are very confused right now after Martha De Laurentiis’s passing. What was the question, again?

HOP: You answered it. People want to know if they’re going to fuck.

As we speak, the US Supreme Court is deciding whether Colorado’s ban on conversion therapy for LGBTQ+ people is constitutional. You’ve been a publicly queer storyteller for decades, navigating different eras of acceptance and backlash. At a time when the LGBTQ+ community is facing renewed hostility from those in power, I want to ask: What does it mean to you to continue making your work right now, and what would you say to the next generation of queer filmmakers and artists?

BF: We are at a pivotal juncture in history, and which way we tip is up to every one of us. This is the time when artists need to be radical. I would divide artists into two categories: the radicals and the sneakies, who are sneaking ideas into mainstream works that will start to pick away at long-held beliefs about who we are as queer people. Then, there are those who get in people’s faces. I think both artists are important. One category of artists needs to alienate the people who dehumanise us and be acrimonious and confrontational. The other category of artists needs to pat the seat and say, ‘Sit down beside me. And this is why you may be queer too—maybe not sexually, but ideologically, humanitarily. You are queer because you don’t always belong.’ There’s something about not belonging that feels so freeing. When you find others with whom you can share that not-belonging, there’s nothing like it.

Dust Bunny releases in US theatres this Friday

“I Knew Mads Mikkelsen Could Do the Hitman Part in His Sleep”: Bryan Fuller on His Film Debut Dust Bunny

Ahead of the release of his first feature, the writer and director discusses collaborating with Mikkelsen and Sigourney Weaver, his family-friendly 80s horror influences, and a potential Hannibal revival

by Heather O. Petrocelli 10 December 2025 Extended interview originally published in Issue 004

Courtesy of Roadside Attractions

Bryan Fuller has never been afraid to walk a tonal tightrope. His genre-bending television has redefined storytelling through sumptuous, grimly romantic imagery and unflinching examinations of death, identity, beauty, and queerness. Pushing Daisies was a “forensic fairytale” defined by a campy creepiness. Hannibal blended a brutal police procedural with a devastating queer romance (between a cannibal and an FBI agent). Now, making the jump from TV to film, his latest work is a twisted fable—part-action, part-horror—with an alluringly simple premise: a little girl (Sophie Sloan) hires a hitman to kill the monster under her bed.

Starring Mads Mikkelsen and Sigourney Weaver, Dust Bunny sees Fuller bring his signature visual splendour to the silver screen. In a sprawling conversation with Heather O. Petrocelli, author of Queer for Fear: Horror Film and the Queer Spectator, Fuller breaks down the making of his directorial debut, his relationship with mortality, and what it means to be a queer storyteller during this moment in US history.

Sophie Sloan as Aurora in Dust Bunny. Courtesy of Roadside Attractions

Heather O. Petrocelli: What drew you to Dust Bunny as your first feature film?

Bryan Fuller: It started as an episode for the Amblin show Amazing Stories on Apple [TV+]. There were a lot of stories I loved that I couldn’t get the executives at Apple excited about. This was one of them. After pushing it uphill for so long, I was like, ‘This would make a really good movie.’ The story is simple, on its surface, and would allow me to do some fun things with the camera as a directorial debut. Then I wrote a feature script, and it lived and died and lived and died… For five years, we tried to make it, and finally, someone was like, ‘We want it.’ And I said, ‘Would you make it with Mads Mikkelsen?’ And they said, ‘Yes.’ A lot of studios that I had been dealing with wouldn’t finance it based on that attachment.

HOP: How did you find the transition from TV to film?

BF: It was relatively organic. The show was an anthology, and we wanted each episode to be an Amblin movie. Because that was the highlight of my summer moviegoing experiences in the 80s: these wonderful high-concept gateway horror children-in-peril stories like The Goonies or Poltergeist. I particularly liked the summer of 1984. There were so many high-concept original movies like Ghostbusters and Gremlins and Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, which was a sequel, but you still got somebody pulling a heart out from a guy’s chest and setting it aflame.

“I still am that kid who loves those big, high-concept stories that have an emotional root.”

So there were now all of these horror elements in mainstream summer movies. My head was exploding because I ate these stories up, and they were coming at me with such rapid fire. I had missed that time—and I still am that kid who loves those big, high-concept stories that have an emotional root. That was the kind of movie that I was chasing as an audience member, and now I got an opportunity to chase it as a filmmaker.

HOP: This next question fits perfectly with what you’ve just said. Dust Bunny is an homage to movies that can both traumatise and initiate kids into the horror genre. But for you, horror movies were a safe space growing up. What is a horror film you saw as a child that made you feel both scared and safe at the same time?

Sophie Sloan and Mads Mikkelsen in Dust Bunny. Courtesy of Roadside Attractions

BF: There were so many. A lot of my earliest impressions of horror movies are tonal as opposed to narrative. When I think about films that disturbed me as a child, I go to things like Let’s Scare Jessica to Death, which is not necessarily a great movie, but it was on cable. Cable that we were stealing from our neighbours. My dad was an electrician and climbed the telephone pole and wired it into our house. So when I was watching these movies, I also knew that it was illegal—and that we couldn’t tell people we had cable because the scary people would come to our house. ‘Are they going to take me to jail because my dad stole Showtime?’ So seeing them on cable had an extra kind of percolation.

In Let’s Scare Jessica to Death, what struck me was the paranoia of the story—that you can’t trust anybody around you. It was very relatable because I grew up in a violent house. The scares were the people under my roof, or one person under my roof. Stories about whether or not you are safe with the people you know—they hit my queerness in a very specific way. Movies like The Other, with the twin boys and the pitchfork in the haystack, those crazy little moments that were about paranoia and safety. I was watching movies where people felt that they, too, were unsafe, and as is illustrated in your book, that speaks to us as queer people.

Those films were the ones that unsettled me. But the ones that I loved were Black Christmas, Jaws, Rosemary’s Baby… I saw them early on stolen cable. They were not necessarily unsafe spaces for me because seeing the protagonists survive monsters, demons, and devils gave me an indication that I was going to survive this home environment as well, as a young queer person who was being identified as queer and being forced out of that queerness with a variety of coercive methods.

HOP: You grew up in Idaho, is that correct?

BF: It’s the Lewis-Clark Valley. So it’s Lewiston, Idaho, Clarkston, Washington. It’s one community. And I grew up in a place where my assistant scoutmaster was a serial killer.

HOP: Excuse me… What?!

BF: All of those things were a factor as I was getting obsessed with horror movies. There was a string of murders. I was eight years old when the first body dropped. They went on for like six or seven years, and all of a sudden, I was a background character in a horror movie. I would ride my bicycle out to the bridge where one of the bodies was dumped, and there were still blood stains in the cement. I was keenly aware of feeling unsafe at home. I felt more unsafe in my home than I did in the community with a serial killer assistant scoutmaster, if that makes sense.

Rebecca Henderson and David Dastmalchian in Dust Bunny. Courtesy of Roadside Attractions

HOP: That makes perfect sense. I like how your love of horror had an extra ‘jolt’, from the stolen cable to your assistant scoutmaster serial killer.

Dust Bunny shows a return to the colourful yet macabre world of Pushing Daisies, while adding action into the mix. How did you approach balancing this unique blend of horror, action, and magical realism?

BF: There was something about the absurdity of a little girl hiring a hitman to kill a monster under her bed that required its own reality. Also, what you don’t see in those worlds becomes part of the reality, which I really enjoy as a storyteller. I sit down and think about all the characters and their points of view, and I try to sew together the DNA of a cohesive reality that they can all share. Then I narrow the perspective and keep it to the emotional focus of the story and the protagonist.

HOP: So, based on everything you’ve talked about with your childhood influences, I feel like horror, action, and magical realism just live naturally in you.

“There was something about the absurdity of a little girl hiring a hitman to kill a monster under her bed that required its own reality.”

BF: I think they do. I remember walking out of the first Terminator in 1984—I was 15—and thinking, ‘God, I wish somebody was trying to kill me. My life is so boring in this small town that has a serial killer.’ I still had the audacity to think that the experience was boring. So A) I wished somebody was trying to kill me, and B) I had a thumping Brad Fiedel soundtrack accompanying my pubescence. Those of us from tricky childhoods have a kind of dysmorphic relationship with horror or action thrillers because we’re living in an unsafe situation, yet we are drawn to narratives about people surviving unsafe circumstances. And it’s not necessarily about my survival because my survival is implicit—I’m the protagonist of this story, and Linda Hamilton makes it to the end of the picture. But that’s the pillow. That’s the cosy pillow that we cuddle because when we go home, survival is a question mark. What I love about having this conversation with you is that you’ve written about all of this so beautifully. It’s been your life’s work.

HOP: I could talk horror with you all day. I’m realising how much our experiences overlap: we’re roughly the same age, so everything you reference hits me just as hard. Same emotional imprints, just in different circumstances. I was a welfare kid with a single mom who moved around a lot. That’s probably why I connect so much to the magical realism in your work—it reminds me of Pan’s Labyrinth.

Your stories often grapple with death, but rarely in a grim way. What do you think our cultural narratives get wrong about death, and what are you trying to reframe through your work?

BF: One of the reasons that I am fascinated with death is that it’s the grand equaliser. We’re all driving toward that inevitable cliff. Growing up with a large extended family, I went to funerals of uncles and great uncles and grandparents. There was something about adults making funerals a safe place for a child because they’re trying to limit the stress of those experiences. And I learned about David Cronenberg from my older cousins at funerals talking about Shivers. So funerals were a place where I got to see my cousins, hear about movies I didn’t have access to, and also feel coddled while surrounded by death in a way that allowed me to look at it as an inevitability.

If there’s something I’m trying to do with the exploration of death in my stories, it’s a simultaneous mystification and demystification of it. Looking at Pushing Daisies, the pie maker can bring somebody back to life, but only for a minute. It still commits to the bit of the inevitability of death, and the consequences of avoiding it will always be more death.

My mom died last year, and it was fascinating to see—I’m the youngest of five—the dynamics of everybody’s mourning process. I gave everybody a coupon to grieve how they need to grieve. But what was curious in our political culture was to look at grief through a MAGA lens, because one of my siblings is MAGA and my mom was not—she was relatively anti-Trump and didn’t understand how she raised a daughter to be MAGA. I realised: ‘This is an interesting study of how opposing viewpoints approach grief’—in a way that was reflective of a selfishness, where you believe your grief is greater than everybody else’s, and you demand that it is yours and yours only. It was eye-opening—how we politicise ourselves is a reflection of our relationship with grief.

Sheila Atim in Dust Bunny. Courtesy of Roadside Attractions

HOP: Grief through the prism of politics. That’s fascinating.

BF: It was wild. And I need to write my August: Osage County about it.

HOP: Throughout your incredible career, you’ve worked with some iconic names in film and television. But I imagine that there’s still deep down that little horror kid who thinks, ‘Holy fucking shit, that’s Ellen Ripley.’

BF: Yes!

HOP: What was it like working with Sigourney Weaver on Dust Bunny, both as a storyteller collaborating with a great actor, and on a personal level working with such a horror icon?

BF: It’s still surreal that I got to work with Sigourney. When we were at TIFF, an interviewer asked a not dissimilar question about the iconography of Sigourney’s roles, not the least of which is Ellen Ripley, and what she means to queer kids growing up and what she meant to me as a queer kid. Because the male heroes were not applicable to me.

But why Ellen Ripley, Princess Leia, Wonder Woman, and Geneviève Bujold in Coma were important to me was because the men were an unsafe space in my experience growing up. Straight white men were the most dangerous for me. I’m explaining this to the journalist, how the power of these women was so inspiring, and Sigourney was like, ‘That is so odd to hear because playing that character, I felt powerless. As a woman, I did not feel like I had my power to ensure my own survival, and that’s why it was a battle.’ I was like, ‘You just nailed it! You just nailed why that is so relatable to queer people.’ Because we see ourselves as powerless as well, whether consciously or unconsciously. Women in these narratives, through the lens of society, are less powerful, yet they find power, they persevere, and they survive. That is the most valuable lesson a young queer person can get: you don’t have any power, but you better fucking find it, or you’re gonna have a second set of jaws smashed through your skull. You have no choice.

We know that Ripley is strong. But it was fascinating to hear from the actor about the reality of who the character is—which is somebody terrified about their survival and still surviving. I mean, because we were having the conversation, there were people in the room crying.

HOP: I’d be remiss if I didn’t say that I’ve been looking at a xenomorph in the background of your room this entire time. I say all this after your story because Alien, unsurprisingly, was the #1 favourite horror film of queers in the Queer for Fear survey.

Dust Bunny poster. Courtesy of Roadside Attractions

BF: Yes, there’s something about it. That’s the reason I came to film school—because I was studying to be a psychiatrist. I was taking an experimental psychology course, and my experiment was: do you get more out of a movie if you experience it as a popcorn thriller, or if you have the added levels of Freudian and/or Jungian analysis that gives you greater insight into what the story is? One thing that appealed to me about Alien was that there was a parental figure, a mother, even though in my home, the father was the problem—but the mother was a guardian entity who betrayed her children for a giant cock. I’ve had conversations with Ridley Scott about the design elements, where he suggested, ‘It wasn’t like that—that was H.R. Giger.’ He kind of waved off the deeper psychological implications of the movie, and he was just there to make pretty pictures and tell a surprising story. But the psychology of it is what makes Alien such a profound movie for me as a filmmaker and a filmgoer. It was the first movie where I was like, ‘That production design is saying something.’

There was something about Ellen Ripley, written as a man played by a woman, that has that gender fuckery that makes her so distinctively queer. When I was reading the novelisation by Alan Dean Foster, I think it was for Aliens, when they were talking about Ripley’s daughter, I was like, ‘She doesn't have a fucking daughter! She is a queer woman with her own identity. She’s not married. She doesn’t have kids. She’s just fucking Ripley. And she doesn’t need that to make her a good human to protect this vulnerable child.’ I was glad when I saw the movie that none of that shit was in it, because I was like, ‘Nope, she’s queer. You’re not taking that away from me.’ And I could go on about vagina doors, penis-headed monsters, male rape, forced birth—all of those things that make it kind of this litmus test of how deep your understanding of a movie can go because, at its surface, it’s Jaws in space, but at its soul, it is queer survival.

HOP: Yes, chef’s kiss. You just talked a lot about production design. From shooting in Budapest to collaborating with production designer Jeremy Reed, how did you approach creating the surreal world of Dust Bunny?

“It’s candy-coloured and candy-coated, so you want to lean in and take a bite and taste the sweetness of the world.”

BF: You know what was interesting about filming in Budapest is that, at the time, a couple of years ago, it was a very homophobic, very racist dictatorship. And, well, we’re there as the United States. But one of the things that I loved about working there is we had an amazing location scout who found us these wonderful buildings that had been recently refurbished—like the Hungarian Treasury, which was the apartment building. And that was a tent pole for our aesthetic in many ways. Jeremy and I had a lot of ideas going in about what the film should be, and we talked about the films of Jean-Pierre Jeunet and Marc Caro and their collaborations —Delicatessen, City of Lost Children, and Amélie—wanting this to feel Parisian in its opulence as a fairy tale and a little bit like the witch’s cabin in the forest. It’s candy-coloured and candy-coated, so you want to lean in and take a bite and taste the sweetness of the world.

One of the cool things was going to these amazing fashion houses in Paris where all of Sigourney’s costumes were being built. So when we went to Paris for Sigourney’s fitting with Catherine Leterrier, an amazing and iconic costume designer in France (and mother of filmmaker Louis Leterrier), we also went wallpaper shopping. I love wallpaper. I love patterns and design. A lot of the conversation was creating the jewel box of this fairy tale, but trying not to do so much that it takes over from Sophie Sloan’s [who plays the lead, Aurora] face, which is the real visual effect of the movie—just her expressive face.

Sophie Sloan in Dust Bunny. Courtesy of Roadside Attractions

We didn’t have a ton of resources. I mean, we weren’t a cheap movie—we were under $20 million. But we also had a monster and a child that we could only work six hours a day with, who was in practically every scene of the movie. So a lot of it was having dedicated people stepping up to the challenges. Our props people in Budapest were fantastic. Our grip, the electric departments, and our gaffer were amazing. One of our camera crew, Ferenc—every morning, because we only had a crane for two days of the 40-day shoot—he was like, ‘How long do you want the crane today?’ And we're like, ‘60 feet.’ And he would start strapping scaffolding together with belts and build a crane every morning from scratch because we had that level of dedication.

So much of the movie is about wounded children. One of my closest friends that I came out of the experience with was Olivier Bériot, who was our costume designer for everybody but Sigourney. Catherine’s retired, but she’s been working with Sigourney since Gorillas in the Mist, so she said, ‘I’ll do Sigourney’s outfits, and then Olivier will do the rest.’ It was a great collaboration. Olivier, when he first arrived in Budapest, was like, ‘Can we have lunch because I want to talk to you about the script and whether you are Aurora, the little girl, or the neighbour.’ And I said, ‘I’m always going to be the little girl.’

There’s a line in the movie that was taken from my childhood. When they ask Aurora about her parents, she says, ‘They weren’t very nice to me.’ And that’s all you get about this child’s history. So the audience can either think they weren’t very nice to her because they didn’t give her cha-cha heels at Christmas, or something worse. It’s up to the audience to decide how they see themselves in this character. So Olivier asked, ‘Who are you?’ and I was like, ‘Well, who are you?’ and he said, ‘I am also the little girl.’ He told me the story of his childhood—that was much more extreme than mine, and mine was fucked up—and I saw the value of people being able to have that conversation after this movie. That’s the thing I hope people can come away with—having a fun moviegoing experience that’s first and foremost a romp, but you can scratch beneath the surface. You can ask bigger questions about your relationship with your childhood home, and how that may have left lingering resentments that you still carry into adulthood. But it is a fairy tale. It is meant for children, but it is also rated R. So don’t ask me to babysit your kids.

HOP: I love that you invite us to project our own stories onto Aurora’s—whether we had a childhood like Dawn Davenport or something far worse.

You’ve described Resident 5B as a hitman with a heart, and said no one but Mads Mikkelsen could play him. What did Mikkelsen bring to the role, and how has your creative relationship evolved since Hannibal?

Mads Mikkelsen in Dust Bunny. Courtesy of Roadside Attractions

BF: I knew Mads could do the hitman part in his sleep. What was more appealing for me, knowing Mads as a human being and sitting with him on weekends while working on Hannibal, is that he really is a professional. I had pitched him this idea when it was going to be an Amazing Stories episode at the premiere of Rogue One years ago, and he was like, ‘Sounds great. I’m in.’ When I met him for the first time, I was like, ‘Oh, he’s a movie star.’ I’ve met a lot of celebrities who don’t have the rizz, as it were, in person. And he has more charisma in person than on screen. I wanted to see more of Mads in the performance because he exudes so much more charisma as Mads Mikkelsen than he does as Le Chiffre or Hannibal. When I shook his hand, I was like, ‘He’s a rockstar.’ He’s sort of like the Danish George Clooney.

What I didn’t realise, because I was so busy thinking how cool he was, was that he also thought I was… not necessarily cool, but worthy of his friendship in a way. There was something about this kid from the Lewis Clark Valley talking to this charismatic movie star and then realising, after doing a show with him and then starting Dust Bunny, that we were friends. Even more than friends—we’re fraternal in many ways. And he always had my back. It was a challenging production, and he stepped up at every turn. There was a certain point where Mads just commandeered the stunt team because he had more stunt experience than anybody else on the movie and knew how to do these things. So we would spend Sunday afternoons choreographing fight sequences with Bruce Lee action figures and mock-ups of the sets, and then filming them and sending them to the stunt team. At every step, he was additive. He would pitch things, I would pitch things, we would play in a way that I was like, ‘He’s my friend. This isn’t just a co-worker.’ I guess the long and short of it is I realised that this guy, whom I’m so impressed with as an actor, was my friend first.

“I wanted to see more of Mads in the performance because he exudes so much more charisma as Mads Mikkelsen than he does as Le Chiffre or Hannibal.”

HOP: So it sounds like you, as his friend, wanted to capture more of Mads for this role. To have more of who he is shine through this work.

BF: Yes. I still want to see Mads because he’s still playing the hitman, and there are moments where he’s so charming with Sigourney. What I loved about them working together is that they both had little crushes on each other. There was this kind of school dynamic where they’re both professionals, so they can’t like fan out on each other. But we’d do a rehearsal and Mads would go to makeup, and then Sigourney would, very gentlewomanly, say, ‘I am very enamoured with our leading man.’ And I was like, ‘Yes, he’s very charming.’ And when Sigourney got up, Mads would express equal yet more—because we have that fraternal relationship—direct expressions of his smittenness with Sigourney that are probably not suitable for print. But that was so cute to see where I was like, ‘Do you want me to pass her a note?’ That dynamic was mutual. I told Sigourney about it, and she blushed and said, ‘Well, you just made my day.’ It wasn’t something I shared while we were filming, but afterwards I was like, ‘That was a real mutual appreciation.’

HOP: This story has made my day. At a time when queerbaiting was rampant, you openly acknowledged the love story between Will and Hannibal. Why was it important for you to canonise that relationship, and are you interested in depicting their romance more explicitly in a potential continuation of the story?

Mads Mikkelsen in Dust Bunny. Courtesy of Roadside Attractions

BF: When I set out to do Hannibal, I wanted to tell a story about heterosexual men who fell in love with each other. And then it became a pansexual in love with perhaps a bi-curious man, and then it became something that was totally queer and about falling in love with the other person as a person first and seeing genitals second, which is something that I’m fascinated by as a cisgender man. I mean, I’m a Kinsey Six, so I’m queer and g-g-g-gay, and so there was something about my own restricted perceptions of my sexuality as a cis six that was eye-opening as well.

I feel like their love and their sexuality in many ways are not gendered because they’re in love with each other. I don’t mean it to be a cop-out or queerbaiting, because I do actually feel like the characters earned their attraction to each other. It didn’t start with that intention, but the attraction was coming through so clearly, and it had to be acknowledged. It just reached a point where we had to either acknowledge or deny it. Denying it felt dishonest; acknowledging it felt like a continuation of their arc. It does feel like an arc interrupted in so many ways, because, as somebody who is… There have been opportunities where I have friends who are couples who have suggested dalliances, and I was like, ‘I’m gay.’ I wish I were bisexual because there are so many things that I find attractive about women, but I’m just a big fag.

“I do think the story [in Hannibal Season 4] would go to a place where there would be physical intimacy between these two men.”

So the length of time it took me to get to that place with the characters was probably because I was finding ways to erode my own parameters of sexual expression. Because I see so much of myself in Will Graham, warts and all. So I was like, ‘Is this guy more fluid than I am?’ And the answer is yes. And Hannibal, in my mind, is as fluid as they come. Beauty is the only determining factor of his attraction. Are you beautiful on the inside? Are you beautiful on the outside? Are you capable of beauty and kindness? That is attractive to him.

As a gay man, there’s so much emphasis on aesthetics and our bodies and how we perceive the world through a version of manhood. I think queer men get sucked into a lot of bullshit with the performance of masculinity that is, just plain speaking, boring. So there was something about these men being attracted to each other’s souls and minds. The fact that we had not yet got to any sort of sexual act… that makes it even hotter for me. But I do think the story would go to a place where there would be physical intimacy between these two men. I hope that we get to tell that story. I think the rights are very confused right now after Martha De Laurentiis’s passing. What was the question, again?

HOP: You answered it. People want to know if they’re going to fuck.

As we speak, the US Supreme Court is deciding whether Colorado’s ban on conversion therapy for LGBTQ+ people is constitutional. You’ve been a publicly queer storyteller for decades, navigating different eras of acceptance and backlash. At a time when the LGBTQ+ community is facing renewed hostility from those in power, I want to ask: What does it mean to you to continue making your work right now, and what would you say to the next generation of queer filmmakers and artists?

BF: We are at a pivotal juncture in history, and which way we tip is up to every one of us. This is the time when artists need to be radical. I would divide artists into two categories: the radicals and the sneakies, who are sneaking ideas into mainstream works that will start to pick away at long-held beliefs about who we are as queer people. Then, there are those who get in people’s faces. I think both artists are important. One category of artists needs to alienate the people who dehumanise us and be acrimonious and confrontational. The other category of artists needs to pat the seat and say, ‘Sit down beside me. And this is why you may be queer too—maybe not sexually, but ideologically, humanitarily. You are queer because you don’t always belong.’ There’s something about not belonging that feels so freeing. When you find others with whom you can share that not-belonging, there’s nothing like it.

Dust Bunny releases in US theatres this Friday