Goodbye, Season of the Witch: Weapons Marks the End of an Era for Feminist Witch Films

Payton McCarty-Simas, author of That Very Witch: Fear, Feminism, and the American Witch Film, unpacks the cultural context behind the breakout villain of the new Zach Cregger film

by Payton McCarty-Simas 15 August 2025

© New Line Cinema

A few weeks ago, I published my second book, That Very Witch: Fear, Feminism, and the American Witch Film, a deep dive into the relationship between the representation of witches in horror movies and the ebbs and flows of American feminism since the 60s. On the book tour, I’ve been getting the same question at every single event, and up until this week, it’s the one that’s been most complicated to answer: Where do witches on screen go from here? In That Very Witch, I contend that at moments of heightened feminist activism (the 60s, the 90s, the 2010s), you often see a proliferation of powerful witches in the horror genre. Given that the witch has been used as a feminist symbol of empowerment since the 19th century, this association makes sense: when women seem to be making genuine progress towards undercutting patriarchal structures, witches become powerful vectors for masculinist anxieties about this potential loss of power, leading to cathartic, deeply feminist depictions of witchy women from Rosemary’s Baby to The Craft to The Witch. But as the fears that underlie that kind of depiction suggest (witches are scary, after all), the witch is also a historically anti-feminist symbol. Thus, I argue, in periods defined by backlash to feminism or moments of resurgent conservatism (the 80s, the 2000s), the way the witch is deployed shifts dramatically: she loses some or all of her power to frighten, often taking on a more comedic cast. Think about the contrast between something like Black Sunday (La maschera del demonio) and something like The Witches. Backlash isn’t so much about literally demonising childless cat ladies—that gives them too much power. Backlash is more often about making us believe that women outside traditional gender roles are sad, ineffectual, pitiable, a little silly. Humour and derision are the best tools of backlash.

© New Line Cinema

Last week, when a woman asked me what was going on with current cinematic witches politically, my answer was: It’s complicated. As I discuss at the end of my book (and as anyone who reads the news already knows), we’re experiencing a period of radical political change characterised by a violent, and thus far tremendously successful, assault on the rights of virtually every marginalised group, not to mention the foundations of American democracy, history, and science. Backlash to feminism has returned with a vengeance, cloaked in a conservative defence of “traditional” (read: conservative, cis, white, or religious) femininity, from Tradwives to Sydney Sweeney. You can also sense this exhaustion in memes about being “just a girl” online, humour that evinces a breezy dissatisfaction with the double standards women face and the burnout of 2010s feminism.

Cinema always responds to the culture on a slight delay (compared to our instantaneous whirlwind news cycles, production schedules are glacially slow), and backlash evolves with the times. Up to this point, I’ve cited the fractal nature of the film landscape to suggest that the 2020s haven’t fully cohered into a legible cinematic “era” for witches yet. Witches on screen are all over the place, from the musical witches of Wicked or the romantic witches of Practical Magic 2 to the 80s-style Satanic witches of films like Bring Her Back and Longlegs. In this kind of landscape, no one depiction felt definitive.

And then I saw Weapons.

This is a film that I can only describe as a changing of the guard for the cinematic witch of our time, a not-so-fond farewell to the feminist witches of the 2010s. I, like everyone, did my best to avoid spoilers for Zach Cregger’s latest mindfuck, but nothing could have possibly surprised me more on a personal level than when Justine (Julia Garner) finds her car vandalised with that most ancient of scapegoating monikers: WITCH in giant, dripping red letters.

© New Line Cinema

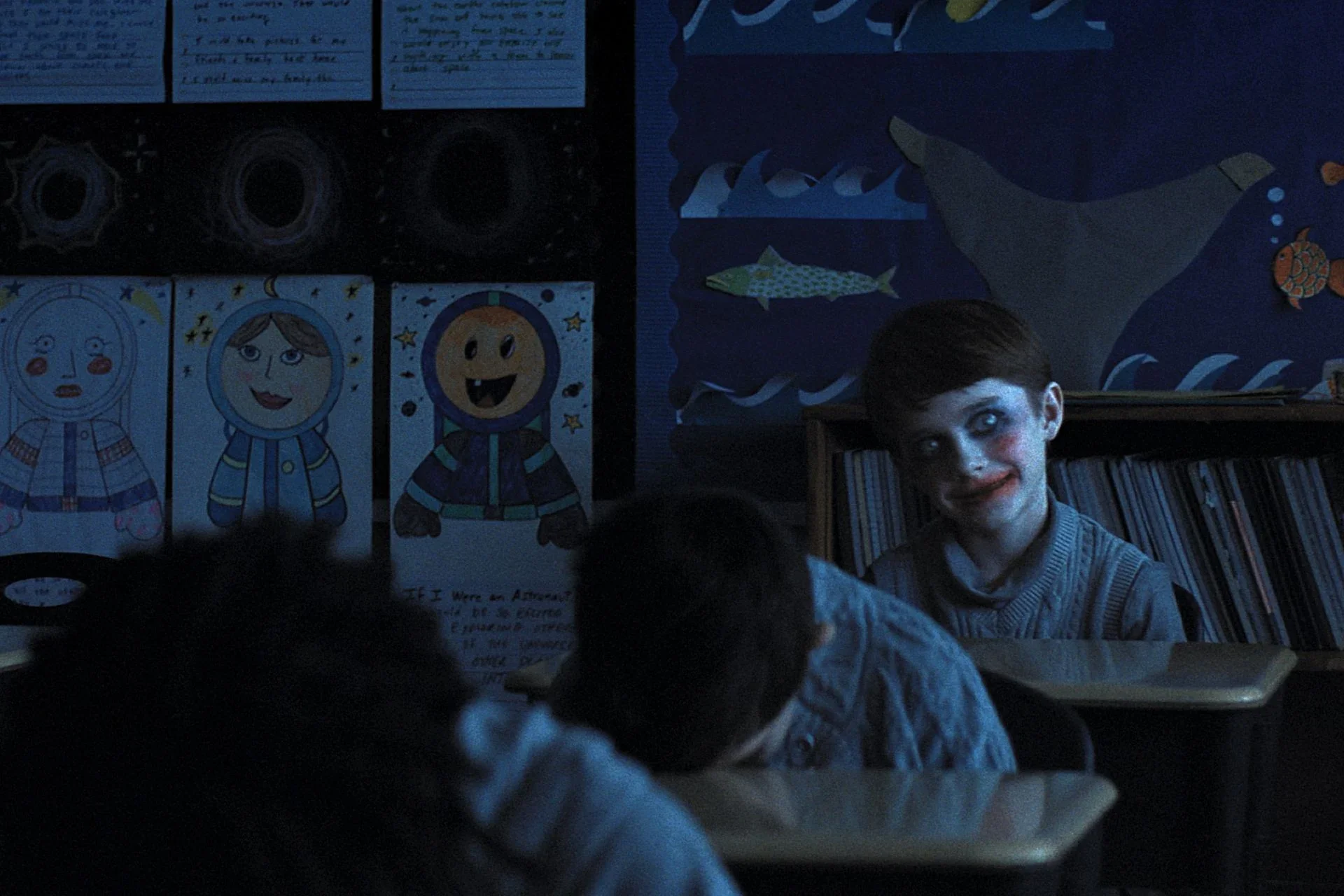

Okay, that’s not true, though finding myself hit over the head with a broomstick by one of the summer’s tentpoles was certainly a shock. After that reveal, I actually felt a comforting sense of familiarity because the opening chapter of Weapons is an almost textbook depiction of the kind of feminist deconstruction of the witch trope that often arrives on the heels of a long witch cycle like the one we experienced in the 2010s with films like Suspiria, Midsommar, and The Witch. In Cregger’s film, Justine, an attractive young single elementary schoolteacher with a drinking problem, arrives to work one day to find that almost her entire class has disappeared without a trace, a premise that actively draws on themes of Satanic Panic through the lens of a Stephen King-ish paperback premise.

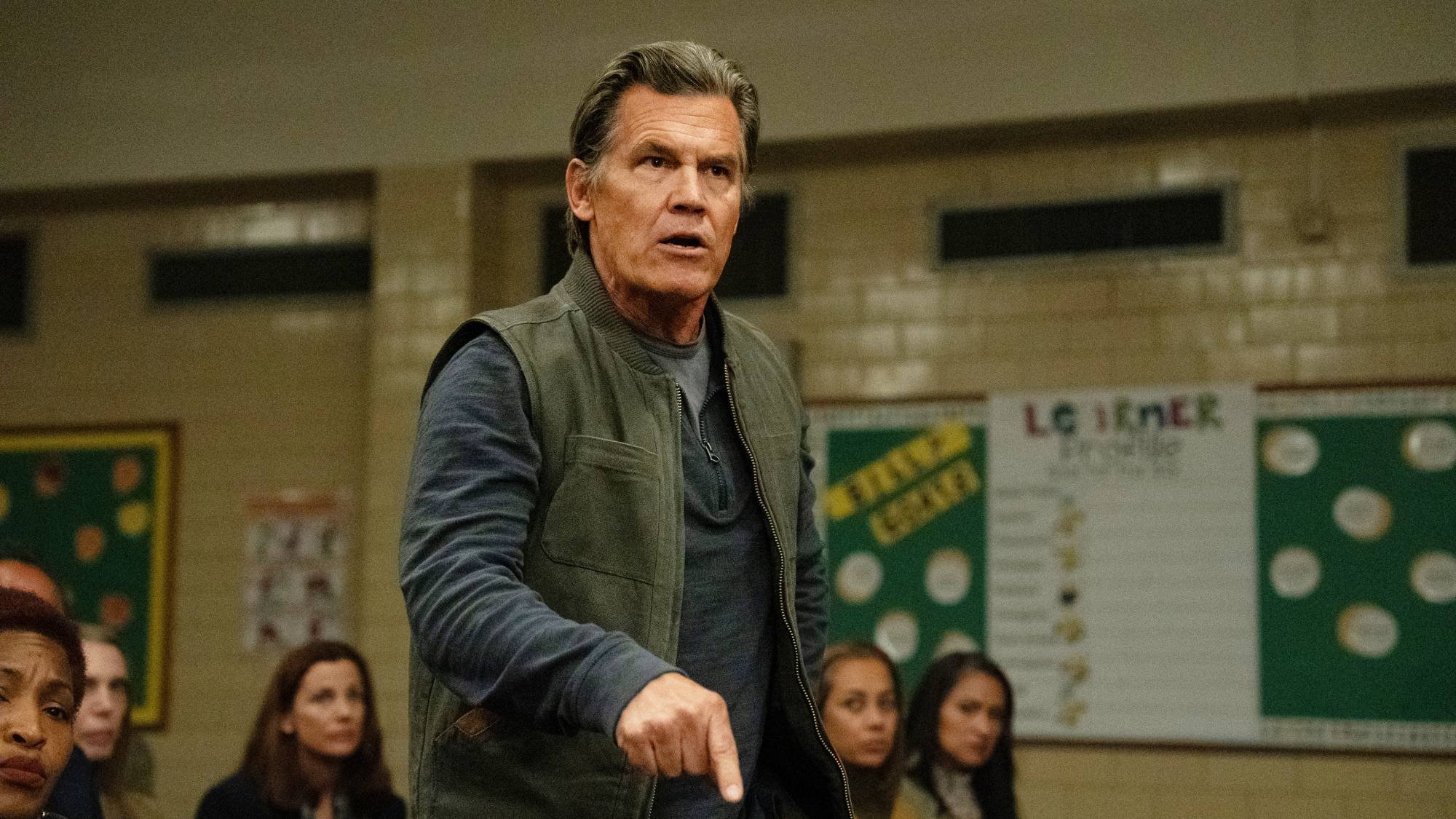

Over the course of the chapter that bears her name, we follow Justine as she’s systematically harassed by her missing students’ parents, stalked, and verbally abused as complicit at best, pedophilic and murderous at worst. A scene at a town hall evokes current debacles concerning “parents’ rights”, and the film goes out of its way to depict the establishment meant to help her as apathetic and absentee. This spare, chilling passage (arguably the film’s best) puts us in a sympathetic position relative to a dynamic, flawed woman whose outsider status marks her a witch in the eyes of a conservative town—a setup that’s almost the same as an excellent 70s-era feminist witch film called The Devonsville Terror which I discuss in the book. Watching Justine, I had some hope that the horror genre would be able to stay the course on presenting witches as a nuanced feminine archetype, frightening and powerful and vengeful and sympathetic all at once.

© New Line Cinema

The real shock of Weapons, then, came in the form of Gladys (Amy Madigan), the film’s actual witch. Sporting a face full of clownish white pancake makeup with a shock of red lipstick smeared over her mouth, Gladys is an equally textbook kind of witch: an evil, child-eating crone. The feminist opening passage turns out to be Cregger’s real head fake, because as it turns out, the conservative parents are right: there really is a witch out to get the kids in this town, she just doesn’t look like Anya Taylor-Joy anymore—she evokes shades of Roald Dahl’s hags or, perhaps for some viewers, phobic visions of drag queen story hour.

Like Anjelica Huston in The Witches or Ruth Gordon in Rosemary’s Baby (an obvious visual inspiration), Gladys is old, mean, and out to steal your kids, destroying any critique of mass hysteria and conservative backlash on display in Justine’s story. If the first chapter reminded me of one of my favourite witch films, The Devonsville Terror, Gladys’ scenes reminded me of one of my least favourite witch films, a misbegotten 80s hagsploitation flick called Wicked Stepmother in which a decrepit Bette Davis comically terrorises a happy nuclear family. Here, the witch becomes a suburban spectre, a way to vent spleen at women who don’t fit a traditional feminine role. Gladys is not, we’re repeatedly told, the “legal guardian” of Alex (Cary Christopher), the last remaining third grader. She’s an unnatural, anti-feminine interloper to this upper-middle-class neighbourhood who turns a contented family home into a pizzagate-style nightmare where zombielike children huddle in the basement and windows are boarded up with newspaper. Her magic is arcane, unsightly, selfish—she seems to feed on souls, preferably children’s (adrenochrome, anyone?), to keep herself alive. Cannibalism, another classical witchy trope, haunts the dinner table as she makes Alex’s parents stab themselves with forks and assures the boy she could make them eat each other if she wanted to.

At the same time, importantly, she’s also pretty funny. This 80s Fright Night throwback concludes with the grotesque sight of the wicked witch, googly-eyed and shrieking, pinwheeling her arms like a geriatric Steve Martin as she’s pursued by an adorably feral horde of her would-be midnight snacks. The children tear her limb from limb, and the crowd sitting around me went wild. All I could think was “sign of the times”.

To be clear, though it may sound odd, I enjoyed Weapons. Like many backlash-era witch movies, Cregger’s film is deeply entertaining, and Madigan’s turn as the Wicked Witch of the Midwest is sensational and instantly, undeniably iconic, an obvious contender for this year’s trendiest Halloween costume. That’s the problem. Weapons is a good film, and its politics are ephemeral, tangled, and at times pleasingly ambivalent—more confusing than damning for a casual viewer. Several of my friends told me they felt that something was off with the depiction of Gladys, they just couldn’t put their finger on why. When talking about witch movies, I tell my audiences to follow the rage: who is it directed towards, and to what end? Where witch-adjacent hagsploitation films like The Substance direct that rage outward, towards patriarchy, here that rage is shockingly boomeranged back again onto that perennial (anti)feminist boogeywoman: the witch. Gladys may be symbolically burned at the stake, but Alex, we’re told, has a new stepmother, and we aren’t sure she’ll be any nicer. Weapons ends by leading us to believe that behind every pristine front door in suburbia, there could be a witch lurking, smeared in makeup and hungry for blood. Woe unto the childless cat ladies.

Goodbye, Season of the Witch: Weapons Marks the End of an Era for Feminist Witch Films

Payton McCarty-Simas, author of That Very Witch: Fear, Feminism, and the American Witch Film, unpacks the cultural context behind the breakout villain of the new Zach Cregger film

by Payton McCarty-Simas 15 August 2025

© New Line Cinema

A few weeks ago, I published my second book, That Very Witch: Fear, Feminism, and the American Witch Film, a deep dive into the relationship between the representation of witches in horror movies and the ebbs and flows of American feminism since the 60s. On the book tour, I’ve been getting the same question at every single event, and up until this week, it’s the one that’s been most complicated to answer: Where do witches on screen go from here? In That Very Witch, I contend that at moments of heightened feminist activism (the 60s, the 90s, the 2010s), you often see a proliferation of powerful witches in the horror genre. Given that the witch has been used as a feminist symbol of empowerment since the 19th century, this association makes sense: when women seem to be making genuine progress towards undercutting patriarchal structures, witches become powerful vectors for masculinist anxieties about this potential loss of power, leading to cathartic, deeply feminist depictions of witchy women from Rosemary’s Baby to The Craft to The Witch. But as the fears that underlie that kind of depiction suggest (witches are scary, after all), the witch is also a historically anti-feminist symbol. Thus, I argue, in periods defined by backlash to feminism or moments of resurgent conservatism (the 80s, the 2000s), the way the witch is deployed shifts dramatically: she loses some or all of her power to frighten, often taking on a more comedic cast. Think about the contrast between something like Black Sunday (La maschera del demonio) and something like The Witches. Backlash isn’t so much about literally demonising childless cat ladies—that gives them too much power. Backlash is more often about making us believe that women outside traditional gender roles are sad, ineffectual, pitiable, a little silly. Humour and derision are the best tools of backlash.

© New Line Cinema

Last week, when a woman asked me what was going on with current cinematic witches politically, my answer was: It’s complicated. As I discuss at the end of my book (and as anyone who reads the news already knows), we’re experiencing a period of radical political change characterised by a violent, and thus far tremendously successful, assault on the rights of virtually every marginalised group, not to mention the foundations of American democracy, history, and science. Backlash to feminism has returned with a vengeance, cloaked in a conservative defence of “traditional” (read: conservative, cis, white, or religious) femininity, from Tradwives to Sydney Sweeney. You can also sense this exhaustion in memes about being “just a girl” online, humour that evinces a breezy dissatisfaction with the double standards women face and the burnout of 2010s feminism.

Cinema always responds to the culture on a slight delay (compared to our instantaneous whirlwind news cycles, production schedules are glacially slow), and backlash evolves with the times. Up to this point, I’ve cited the fractal nature of the film landscape to suggest that the 2020s haven’t fully cohered into a legible cinematic “era” for witches yet. Witches on screen are all over the place, from the musical witches of Wicked or the romantic witches of Practical Magic 2 to the 80s-style Satanic witches of films like Bring Her Back and Longlegs. In this kind of landscape, no one depiction felt definitive.

And then I saw Weapons.

This is a film that I can only describe as a changing of the guard for the cinematic witch of our time, a not-so-fond farewell to the feminist witches of the 2010s. I, like everyone, did my best to avoid spoilers for Zach Cregger’s latest mindfuck, but nothing could have possibly surprised me more on a personal level than when Justine (Julia Garner) finds her car vandalised with that most ancient of scapegoating monikers: WITCH in giant, dripping red letters.

© New Line Cinema

Okay, that’s not true, though finding myself hit over the head with a broomstick by one of the summer’s tentpoles was certainly a shock. After that reveal, I actually felt a comforting sense of familiarity because the opening chapter of Weapons is an almost textbook depiction of the kind of feminist deconstruction of the witch trope that often arrives on the heels of a long witch cycle like the one we experienced in the 2010s with films like Suspiria, Midsommar, and The Witch. In Cregger’s film, Justine, an attractive young single elementary schoolteacher with a drinking problem, arrives to work one day to find that almost her entire class has disappeared without a trace, a premise that actively draws on themes of Satanic Panic through the lens of a Stephen King-ish paperback premise.

Over the course of the chapter that bears her name, we follow Justine as she’s systematically harassed by her missing students’ parents, stalked, and verbally abused as complicit at best, pedophilic and murderous at worst. A scene at a town hall evokes current debacles concerning “parents’ rights”, and the film goes out of its way to depict the establishment meant to help her as apathetic and absentee. This spare, chilling passage (arguably the film’s best) puts us in a sympathetic position relative to a dynamic, flawed woman whose outsider status marks her a witch in the eyes of a conservative town—a setup that’s almost the same as an excellent 70s-era feminist witch film called The Devonsville Terror which I discuss in the book. Watching Justine, I had some hope that the horror genre would be able to stay the course on presenting witches as a nuanced feminine archetype, frightening and powerful and vengeful and sympathetic all at once.

© New Line Cinema

The real shock of Weapons, then, came in the form of Gladys (Amy Madigan), the film’s actual witch. Sporting a face full of clownish white pancake makeup with a shock of red lipstick smeared over her mouth, Gladys is an equally textbook kind of witch: an evil, child-eating crone. The feminist opening passage turns out to be Cregger’s real head fake, because as it turns out, the conservative parents are right: there really is a witch out to get the kids in this town, she just doesn’t look like Anya Taylor-Joy anymore—she evokes shades of Roald Dahl’s hags or, perhaps for some viewers, phobic visions of drag queen story hour.

Like Anjelica Huston in The Witches or Ruth Gordon in Rosemary’s Baby (an obvious visual inspiration), Gladys is old, mean, and out to steal your kids, destroying any critique of mass hysteria and conservative backlash on display in Justine’s story. If the first chapter reminded me of one of my favourite witch films, The Devonsville Terror, Gladys’ scenes reminded me of one of my least favourite witch films, a misbegotten 80s hagsploitation flick called Wicked Stepmother in which a decrepit Bette Davis comically terrorises a happy nuclear family. Here, the witch becomes a suburban spectre, a way to vent spleen at women who don’t fit a traditional feminine role. Gladys is not, we’re repeatedly told, the “legal guardian” of Alex (Cary Christopher), the last remaining third grader. She’s an unnatural, anti-feminine interloper to this upper-middle-class neighbourhood who turns a contented family home into a pizzagate-style nightmare where zombielike children huddle in the basement and windows are boarded up with newspaper. Her magic is arcane, unsightly, selfish—she seems to feed on souls, preferably children’s (adrenochrome, anyone?), to keep herself alive. Cannibalism, another classical witchy trope, haunts the dinner table as she makes Alex’s parents stab themselves with forks and assures the boy she could make them eat each other if she wanted to.

At the same time, importantly, she’s also pretty funny. This 80s Fright Night throwback concludes with the grotesque sight of the wicked witch, googly-eyed and shrieking, pinwheeling her arms like a geriatric Steve Martin as she’s pursued by an adorably feral horde of her would-be midnight snacks. The children tear her limb from limb, and the crowd sitting around me went wild. All I could think was “sign of the times”.

To be clear, though it may sound odd, I enjoyed Weapons. Like many backlash-era witch movies, Cregger’s film is deeply entertaining, and Madigan’s turn as the Wicked Witch of the Midwest is sensational and instantly, undeniably iconic, an obvious contender for this year’s trendiest Halloween costume. That’s the problem. Weapons is a good film, and its politics are ephemeral, tangled, and at times pleasingly ambivalent—more confusing than damning for a casual viewer. Several of my friends told me they felt that something was off with the depiction of Gladys, they just couldn’t put their finger on why. When talking about witch movies, I tell my audiences to follow the rage: who is it directed towards, and to what end? Where witch-adjacent hagsploitation films like The Substance direct that rage outward, towards patriarchy, here that rage is shockingly boomeranged back again onto that perennial (anti)feminist boogeywoman: the witch. Gladys may be symbolically burned at the stake, but Alex, we’re told, has a new stepmother, and we aren’t sure she’ll be any nicer. Weapons ends by leading us to believe that behind every pristine front door in suburbia, there could be a witch lurking, smeared in makeup and hungry for blood. Woe unto the childless cat ladies.