What Justin Tipping Got Right with Him

Despite the crumbling plot, Him’s coded imagery offered a rich exploration of body politics and celebrity worship

by Caro C. 18 October 2025

© Universal Pictures

By now, you’ve likely seen that the jury is out on Justin Tipping’s Him. Despite the hype fostered by the trailers and buzzy press run, the Jordan Peele-produced movie overpromised on the storyline and overall narrative. Marlon Wayans, who plays the larger-than-life American football player Isaiah White, has already made an Instagram post in response to critics’ near-unanimous panning of the movie, pointing out that other critically-maligned films that he has starred in (White Chicks, Scary Movie) have gone on to be classics.

But where Tipping really does deliver is in the subtext, with religious and historical references to tackle themes of perverse celebrity worship and tortured body politics.

© Universal Pictures

The depth of religious ruin

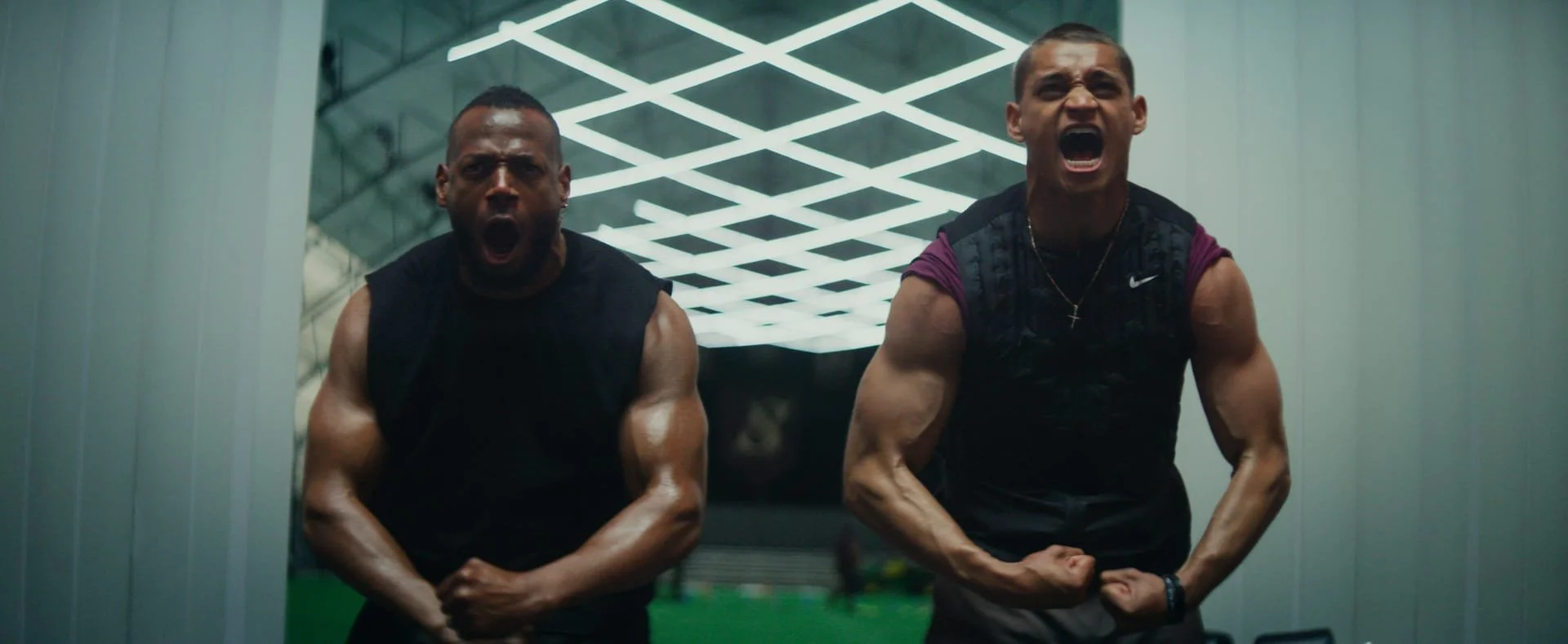

Him takes the concept of celebrity veneration to the max. Monkeypaw Productions had already hinted at this particular visual motif in the movie’s promotional materials—apart from Wayans’ freaky gaze and snarling smile, we got Tyriq Withers, who plays volatile young upstart Cameron Cade, with his arms outstretched in a pantomime of a crucifix.

In fact, Cameron’s athletic trials and tribulations are framed as if he is Jesus or at least, the Second Coming of Him. Isaiah even ribs Cameron by calling him “the prodigal son”—and so the chosen one trope is reiterated in both the plotline and the spiritual imagery.

But if Cameron is Jesus, then Isaiah is certainly Lucifer—cast out from national football heaven. It’s worth noting that the training camp arc of the film doesn’t just take place in some glossy, pristine athletic facility within Isaiah’s compound. A pivotal part of Cameron’s endurance training involves shooting guns and running for miles across the arid expanse of Isaiah’s estate. Anyone raised in the culture of the American evangelical Christian church can’t help but think of every fire-and-brimstone pastor’s favourite Biblical anecdote: Matthew 4:1-11, when the devil leads Jesus to the wilderness to test him. Like Isaiah, the devil seeks to weaken Jesus so that he submits to him and inherits all the world’s splendour.

And that opulence is on full display, from the minimalist brutalist beige home, to the Hollyweird white spouse played by the charming Julia Fox. Opulence is visible in the way Isaiah and his wife, Elsie, command unquestioned loyalty from wannabes and groupies. Tipping really hammers his point home when, at one point, the signing day revellers are arranged in a tableau that resembles Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper.

The concept of indulgence even translates to cinematographer Kira Kelly’s lush visuals; the devil takes Jesus to the desert, and it looks like an Oakley sunglasses ad. The devil also runs football drills in his athletic complex, playing twisted games that leave a San Antonio Saviors benchwarmer bloody, toothless, and concussed. It has the desaturated slickness of a Nike ad.

© Universal Pictures

Both these brands are prominent in the film. Is it immersive? Or does it take you out of the moment, making you feel more like you’re watching your favourite rapper’s latest big-budget music video? Either way, the product placement is fitting: Influencer culture is modern-day idolatry. But Him doesn’t rely solely on Christian imagery to bring its point home.

Often, viewers see cursed figures in clusters of three. These visuals mimic the Weird Sisters that accosted Macbeth, which is a nod to the Three Fates of Greek Mythology. This centuries-old archetype signifies the life, death, rebirth and a murky, ever-shifting destiny. The occult also recurs in Him’s visuals. In Cameron’s final battle, where he’s up against the football league’s bigwigs, he’s standing on a platform that looks like a pentagram with an infinity symbol in it. The curves of infinity within the pentagram bring to mind the goat’s ears of the Sigil of Baphomet. The goat is the universal sign of the devil.

Characters in Him constantly talk about being the “GOAT” or the “greatest of all time.” In AAVE, “I’m him!” is synonymous with “I’m the GOAT!” The central question is whether Cameron has the gall to make that ultimate Faustian sacrifice to be the GOAT.

One sneaky nod to this: in the final confrontation between Isaiah and Cameron, the circular door of Isaiah’s lair room slides shut and viewers see a symbol gilded into the wood. This squared circle is the alchemical rune for the Philosopher’s stone, the alleged key to eternal life.

© Universal Pictures

A history of exploitation

Alongside the celebrity worship depicted in Him is a punishing, physical brutality. This is the nature of performing arts and professional sports—especially when you’re a person of colour.

In his first meeting with Cameron, Isaiah hints at the tie between white supremacist exploitation and brown bodies when he talks about the Native American history behind football. (White settlers in the U.S. were extractive regarding lacrosse as well; the sport created by indigenous people is now a status symbol of the white elite.)

But indigenous Americans aren’t the only ones whose oppression is mirrored in sports. A film heavy on subtext, Him explores the parallels between slavery and how football operates in the U.S. on the field, in the boardroom, and in the court of public opinion. Exploited, overworked black bodies do the vast majority of labour, only to see a margin of the profits—most of which are gobbled up by white proprietors.

And while the physical and mental well-being of players remains neglected, the machine is too vast and too integral to be shut down or even reformed. Earlier this year, President Donald Trump’s administration sought to cut funding for traumatic brain injury research. It’s unsurprising that a White House whose party leaders are vocal about “business interests” would prioritise profit over people—especially Black people, who they so clearly deem disposable.

© Universal Pictures

Where Him could have expounded further

While many viewers are recovering from the broken promise of a film that could have been great, Him can serve as a starting point for crucial conversations about body politics, white supremacy, and parasocial relationships.

But that’s all it is: a starting point. Apart from clunky writing and a rushed ending, the choice to just give viewers one good week in this storyline feels misguided. Perhaps Tipping lingers too long on the hazing at training camp. Viewers get to “ooh” and “ahh” over the lengths Cameron will go to be “goated," but what would have been more compelling is seeing a grateful-but-uneasy Cameron navigating his budding football career. What would have been more compelling is to see how an ambitious, grateful, but ultimately uneasy and reluctant Cameron would navigate his budding football career. How would he handle temptation, beyond Elsie’s nearly-naked girl gang? Professional athletes, especially in the American South, it seems, are always getting caught up at the club.

Would Cameron turn to substance abuse to cope with the guilt and the pressure, or a demonic voice in his head? How would Cameron navigate the tightrope of the public eye, especially as a mixed-race man or, as Isaiah gleefully puts it, a Halfrican-American? Would his body eventually fail like so many other athletes’ corporeal forms? And would his torn ACL or shot knee or chronic traumatic encephalopathy lead him to Satanic bloodletting?

Apart from the visuals, this film was a letdown, especially when it had been touted as another entry in Jordan Peele’s socially conscious but artfully terrifying cinematic universe.