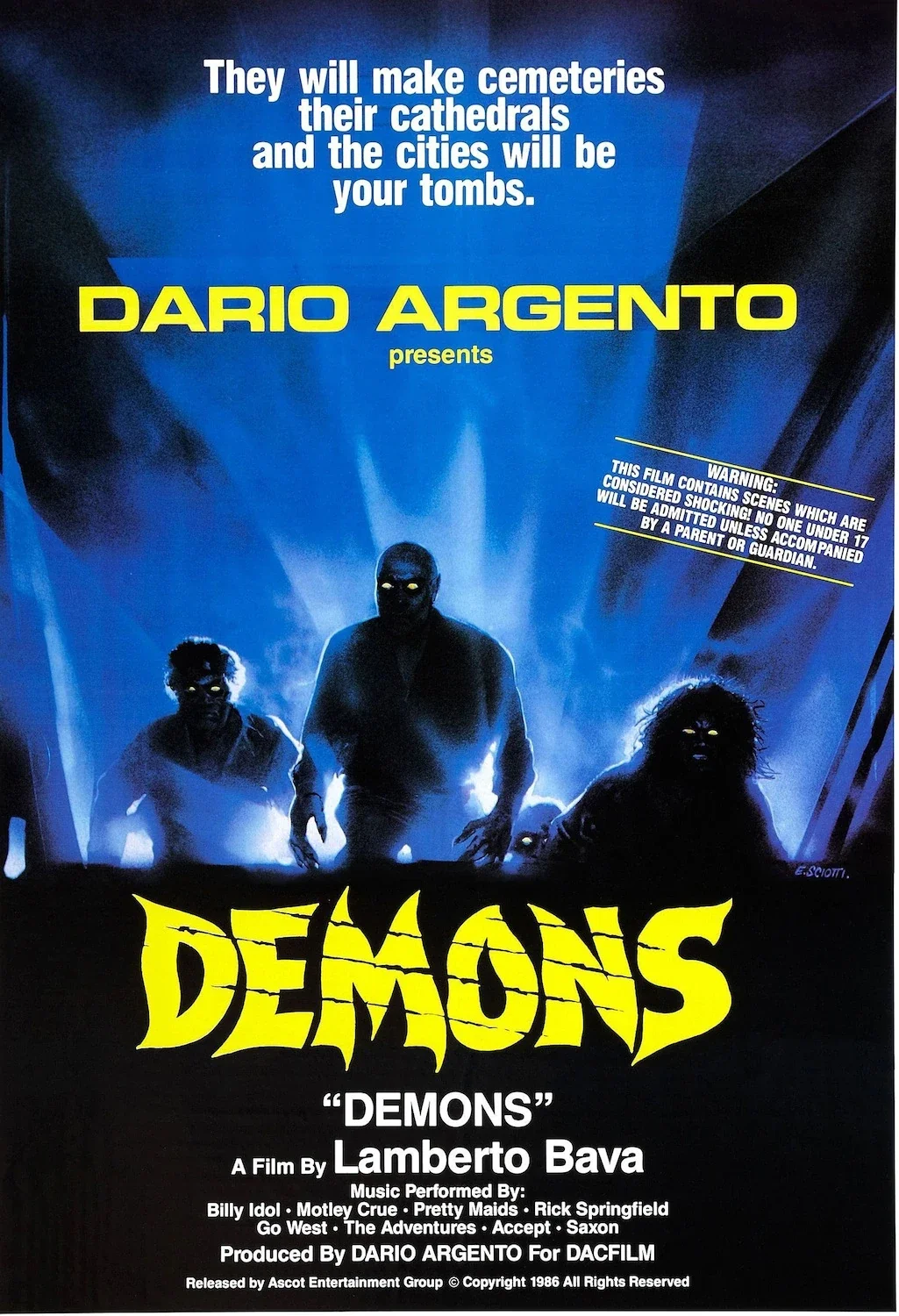

Four decades after its release, Italian genre film specialist Rachael Nisbet revisits the Argento-produced splatter classic and its demented vision of horror spectatorship

Demons at 40: Cinema as Contagion

by Rachael Nisbet 4 October 2025

© DACFILM Rome

In 1985, Lamberto Bava’s Demons (Dèmoni), produced and co-written by Dario Argento, transformed the simple act of going to the pictures into a splatter-soaked nightmare of demonic outbreak and apocalypse. Set almost entirely inside a single movie theatre, Berlin’s The Metropol, it literalises the perennial fear that horror might “infect” its audience. The conceit is disarmingly blunt: a group of local cinemagoers are lured to a free preview, only to discover that the horror on screen bleeds into their reality, mutating them into monsters.

Forty years later, Demons occupies a singular place in Italian genre cinema. It is cherished as one of the most vivid allegories of horror spectatorship ever staged, and remembered for its delirious fusion of splatter, fluorescent glare, and the decade’s moral panics. To revisit the film today is to see a cultural artefact that is both unmistakably of its moment—suffused with the sounds and anxieties of the mid-1980s—and unexpectedly prescient in its commentary on media, contagion, and the collapse of boundaries between screen and spectator.

© DACFILM Rome

Origins and Excess

The origins of Demons lie in Lamberto Bava’s abandoned idea for an anthology segment about monsters emerging from a cinema screen. Expanded with screenwriter Dardano Sacchetti into a standalone feature, the project eventually drew Argento, who reshaped the script, injected spectacle, and ensured international distribution. The collaboration was fraught—Sacchetti was paid off and dismissed, only to be recalled when Argento and fellow writer Franco Ferrini restructured the screenplay. Ferrini, in particular, pressed to delay the first outbreak for maximum tension. The push-and-pull between Sacchetti’s pulp instincts and Argento’s commercial calculation lent the finished film its peculiar rhythm, a slow burn suddenly detonating into all-out chaos.

Production unfolded over nine weeks in the summer of 1985, split between Rome soundstages and West Berlin locations. The choice of Berlin was partly practical—co-production incentives and striking architecture—but it also lent the film a Cold War eeriness, the U-Bahn tunnels and shadowed plazas echoing its themes of confinement and surveillance. Interiors were largely constructed at De Paolis Studios in Rome, arranged as a labyrinth of confinement that turned the Metropol into a maze of panic where escape always seemed just out of reach.

Effects artist Sergio Stivaletti gave the film its signature grotesqueries: teeth pushing through gums; eyes glowing with improvised reflective paper lenses; bile and slime pumped through hidden tubing to drench the Metropol in excess. Resourceful as much as spectacular, his effects had more in common with carnival theatre than Hollywood animatronics—messy and improvisatory, visceral through their imperfection.

Michele Soavi, Argento’s protégé, directed the “film-within-the-film” inserts and appears as the silver-masked ticket taker, a silent emissary who ushers the unsuspecting audience toward damnation. His dual role, behind and in front of the camera, foreshadowed the career he would soon build with Stage Fright and The Church, works that carried forward Demons’ collision of spectacle and self-awareness.

© DACFILM Rome

Splatter Meets Subculture

Beyond its production, what marks Demons so vividly as a product of 1985 is its entanglement with the subcultures of the time. The film’s audience includes punkish delinquents, leather-clad youth, and a flamboyant pimp, each signalling the social anxieties of urban life. Their style (dressed in studs and chains) and their behaviour (from snorting cocaine through a Coke can to brawling in the aisles) root the film in a recognisable youth culture already demonised in the press.

The soundtrack veers between Claudio Simonetti’s synth score and contributions from Mötley Crüe, Billy Idol, and Accept—a deliberate courting of MTV-era energy. In its most notorious sequence, George mounts a motorcycle and slices through the horde with a katana, while Accept’s riotous heavy metal track “Fast as a Shark” blares. It is a moment at once absurd and exhilarating, fusing splatter cinema with the rhythms of the music video, as if the cinema itself has become an MTV stage.

This fusion of horror and metal positions Demons within a wider moment of moral panic over “corrupting” youth culture, from the PMRC (Parents Music Resource Center) hearings on rock lyrics in the US to the “Video Nasty” debates in the UK. Bava and Argento take those anxieties literally—here, music and cinema really do turn the audience into monsters.

© DACFILM Rome

Infection and Entrapment

For all its pop-cultural surface—the punks, the metal, the MTV excess—Demons also trades in deeper anxieties. Beneath the relentless gore lies a set of resonant themes. The most obvious is contagion. Like Romero’s zombies, the demons spread through bites and scratches, transforming a confined space into a site of infection. The Metropol becomes a metaphorical quarantine zone: doors bricked up, exits sealed, the patrons trapped as unwilling participants in an experiment.

This sense of surveillance and manipulation is reinforced by the masked figure who distributes tickets, by the inexplicable entrapment of the audience, and by the presence of a blind man among the spectators—a reminder that vision is incidental when the auditorium itself is weaponised. Sight or blindness makes no difference: once the film begins, everyone is implicated. In this way, Demons reframes spectatorship as a state of exposure. To watch, or merely to be present, is to risk contamination.

The film also speaks to the aesthetics of excess. Its transformations echo the body horror of An American Werewolf in London, but push further into Grand Guignol exaggeration. Blood sprays not with verisimilitude but with operatic force. The spectacle is the point. Argento, in particular, was keen to create what he called a “commercial” horror film, and Demons obliges, offering a carnival of mutation.

© DACFILM Rome

Cinema that Consumes [spoilers ahead]

The most striking dimension of Demons is its reflexivity. By situating the horror within a cinema, Bava collapses the boundary between diegetic world and cinematic frame. The audience within the film becomes the audience on screen, their fate a mirror of our own act of viewing. When a demon literally tears through the movie screen, fiction erupts into reality.

In this respect, Demons anticipates later meta-horror, from Wes Craven’s New Nightmare to Scream. But it is less ironic than those films. Its self-awareness is blunt, almost naïve, yet radical: spectatorship here is not so much satirised as it is obliterated. The Metropol ceases to be a safe vessel for fiction; it becomes a site of ritual sacrifice, with the spectators themselves as the offering.

The ending extends this collapse further. Survivors escape the cinema only to discover the apocalypse has spread beyond. There is no outside, no safe reality to return to. Horror has overflowed its bounds, contaminating the world itself.

The Spread of Demons

Appropriately, Demons proved as infectious off-screen as on. The film’s success led swiftly to Demons 2 (1986), which relocated the contagion to a high-rise apartment block and extended the conceit through television transmission. While less impactful, the sequel reinforced the central theme: horror as media that cannot be contained. In the decades since, Demons has thrived on VHS shelves, midnight screenings, and festival retrospectives, securing its reputation as a cult landmark of 1980s horror.

What makes Demons endure is precisely its exaggeration. Cinema stripped to its essentials—an assault of sound, light and viscera—it both revels in and reflects upon the act of horror consumption. Forty years on, it reminds us that to watch horror is to enter a pact: to risk being changed, unsettled, perhaps even possessed. Bava’s film remains faithful to that promise, a splatter-soaked reminder of cinema’s power to breach its frame and engulf us whole. .