20 Years of Supernatural: Looking Back on the Road So Far with Jerry Wanek

The production designer, co-producer, and director reflects on the record-breaking horror series

by Lana Thorn 18 December 2025 Extended interview originally published in Issue 004

Courtesy of Jerry Wanek

Over 15 years and 327 episodes, Sam and Dean Winchester saved people and hunted things across the United States. Driving in a black 1967 Chevrolet Impala, they stopped by Heaven, Hell, and nearly 200 motel rooms—and practically every detail in those many sets, from wallpaper postcards, was designed by Jerry Wanek.

Along with his art department, week after week, Wanek transported viewers into the world of Supernatural. Aside from the blend of horror, rock music, and brotherly banter, the cult series is known for its Americana aesthetic. But as die-hard fans will tell you, the CW series was shot almost entirely in Vancouver, with Wanek meticulously crafting each diner, billboard, and gas station to deceive the audience.

Supernatural concluded in 2020, making it the longest-running genre show in US television history. Five years and a few TV shows later, the 71-year-old production designer calls me over Zoom from his home in Jupiter, Florida. Taking a break from his painting (he’s contributing pieces to SPN actor Misha Collins’ charity, Random Acts), Wanek discusses his favourite motel room, how Jensen Ackles made him ditch Criminal Minds to join the show, and why Supernatural is more popular now than ever.

Wanek on a set from Season 15, Episode 19, “Inherit the Earth”

Lana Thorn: Before we dive into Supernatural, I wanted to ask: Do you have an early memory of realising you were a creative person?

Jerry Wanek: I grew up in a big family in Wisconsin, and I definitely didn’t fit in. I was off the rails—if it had been today, I would have been on everything: Ritalin, Adderall… Nobody from our small town was an artist, and my dad was very pragmatic. He built houses, and he did some designing when it was called for. Some of my earliest recollections are sitting across from him when he was drawing blueprints, and I would have a piece of paper and try to emulate that.

P: How did you get into the film industry?

JW: After I moved to LA, I managed a bar, and when people in the film business came in, I would beg them for a job. One day, there was a fire at this production house, and they needed somebody to clean it up. I said, ‘I’ll do it!’ They had this big McDonald’s commercial coming up, and they said, ‘Well, if Jerry’s willing to clean up that crap after the fire, let’s give him a shot.’ And that was my first job: getting Ronald McDonald coffee—and Heineken. I worked my way up to first assistant director, but I was always gravitating towards the art department.

Courtesy of Jerry Wanek

P: How did you end up as a production designer?

JW: I worked with an amazing production designer named Vance Lorenzini, who did the Madonna ‘Express Yourself’ video. There was a lot of creative freedom in doing music videos: we did these huge sets. Then I worked with Tim Newman, this fantastic director who did all the ZZ Top videos—and ZZ Top ruled original MTV. It was “Viva Las Vegas”, and his production designer—whom I was working with—wasn’t available. Next thing I knew, I was on a plane to Las Vegas. I didn’t sleep. It was the hardest thing I've ever done. But now I had the creative freedom again, and I just thought, ‘I need more of that.’

I established myself, but when you’re doing music videos and commercials, you can’t do film or TV because you haven’t done it yet. It’s these catch-22s. Then Kenny Rogers gave me a shot with The Gambler, and all of a sudden, I was the Western guy. Even though I always liked more modern, minimalist stuff. I did several Westerns with Larry McMurtry (who wrote The Last Picture Show and Brokeback Mountain), and the textures, the different colours and layers in those films—I can see it now in everything I do. I liked the depth and the age. When we do a set, nothing can be new. I never really wanted to do TV, but once I did The Magnificent Seven, I was working on something for 10 months rather than spending a week on a commercial. I got to tell a story, and that’s the most important thing about designing.

Jensen Ackles in Dark Angel. Courtesy of Jerry Wanek

P: What was the transition like from working on those Westerns to a sci-fi show like Dark Angel?

JW: That was tough. Mark Freeborn—who’s a brilliant designer, he did Breaking Bad and some of The X-Files—had done the pilot, but he didn’t want to do the show. I think he was fed up with [James] Cameron and Fox at the time. When Cameron okayed me, my agent said, ‘You know, he likes to fire production designers.’ But it turned out really well. He came up and directed the last episode, and that opened my eyes. A lot of people like to badmouth Cameron, but you work alongside him, and you’re in awe. No one works harder; no one is more focused. I’ve never seen anybody as intelligent in any subject matter.

P: How did you get involved in Supernatural, and what attracted you to the series?

JW: I had just done the pilot for Criminal Minds when I got a call from my agent. He goes, ‘There’s a show up in Vancouver that Jensen Ackles is gonna be on.’ And I said, ‘I’ll take it.’ I didn’t know the name; I didn't know anything. But my experience watching him on Dark Angel was that he stole every scene. He was so charismatic, and he was such a good actor, that I was thinking, ‘This is the guy you want to hook your wagon to.’ That was the smartest move I ever made. I’m not that big a fan of horror and gore, but I got to use all the things that I love about set design: textures, colours, and layers. I wanted to do cool, creepy places and abandoned churches, and we built almost all of those sets.

The thing about Supernatural is, you can't go into somebody’s house—even if you find a house big enough to shoot in—because you throw people through the walls or splatter blood. It got to a point, halfway through the first year, where [creator Eric] Kripke said, ‘We’ll just build it.’ They’d say, ‘Let Jerry and the art department figure something out.’ That was fun, and also more pressure, but it was great.

Courtesy of Jerry Wanek

P: What is something that you find to be misunderstood about the role of a production designer?

JW: No one knows what it is! They really don’t know. It goes like this, ‘Oh, you’re a production designer.’ ‘Yeah, I oversee the look of the film.’ ‘Oh, so you design sets?’ ‘Well, that’s part of it, but really, I oversee eight set designers and props…’ The biggest thing I tell PDs who worked under me is: ‘Just tell the story.’ You know Bob Singer, who was the showrunner and captained the ship for all 15 years of Supernatural, that was his mantra. When I got the opportunity to direct and was crazy nervous, that’s what he told me: ‘Just tell the story.’ Because it’s tempting to do something wild, but if it has nothing to do with the story, you haven’t done your job.

Courtesy of Jerry Wanek

P: Early on, Warner Bros. was considering a deal with Motel 6. Why did you push back on the deal and fight to design the motel rooms yourself?

JW: Episode 2 or 3, they said, ‘We’re going to make a deal and build one motel room, so wherever you go, you can have a standing set.’ I said, ‘Well, you can do that. But you’re gonna need a different art department.’ Because this was the only way of telling the audience where we were, to give them a sense of place. We always wanted the motel rooms to have something to do with the city or the state. Even today, when I talk to people, they say, ‘Wow, you went all over the place.’ I go, ‘We never left Vancouver!’

Courtesy of Jerry Wanek

I remember the first room we did—I love quirky Americana, and I thought, ‘This is gonna be cool.’ And what I do most of the time is open the set. I’m there the first time the crew comes in, and later when the cast comes in. So I’m sitting in the background, and Jared and Jensen walk in, but they just start doing their blocking, never looking around [to appreciate the set]. I said, ‘Okay, we’re gonna fix that.’ We just kept pushing it and pushing it, and we had so much fun. I remember after only Season 1, after 15 motel rooms, we thought, ‘We’re gonna run out of ideas.’ We ended up doing 173.

In terms of quirkiness, the most famous one in Season 1 was the disco motel. I hadn’t told Phil Sgriccia, who’s a great director and a good friend, what I was doing. He opens the door before the cast gets there, and he goes, ‘Holy cow! ’ So he says, ‘Now I have to put a camera inside, and when the boys open it, we can get a visceral reaction.’ And they did have one. They immediately started disco dancing, and next thing you know, they’re jumping and dancing on the beds. But if you look at that motel room and pick it apart, everything in there has a purpose, including the dance steps to the Hustle, which are on the back of the door. So if you’re gonna go all out, you gotta support it. And everybody got on board. My decorator, George Neuman, and my graphic artists, who are the best on the planet: Lee Anne [Elaschuk], Mary Ann [Liu], and Eric [Jorgensen].

© Warner Bros.

P: Do you have a favourite motel?

JW: There are probably a dozen. I like a lot of the more kitschy ones—the Route 66 one with the mudflap girls. The disco one is certainly up there… But there are so many of them, and everybody had a say in them. The way I run my art department, I never had an office—it was a bullpen. So I could hear everybody, and the best idea wins. My philosophy was that these people were all very accomplished artists. We’d get a nice bottle of wine, and whoever had the best idea of the week would get the wine. It really helped with our look, especially with sustaining for as long as we did. So basically, I stole all their ideas and said they were mine.

Courtesy of Jerry Wanek

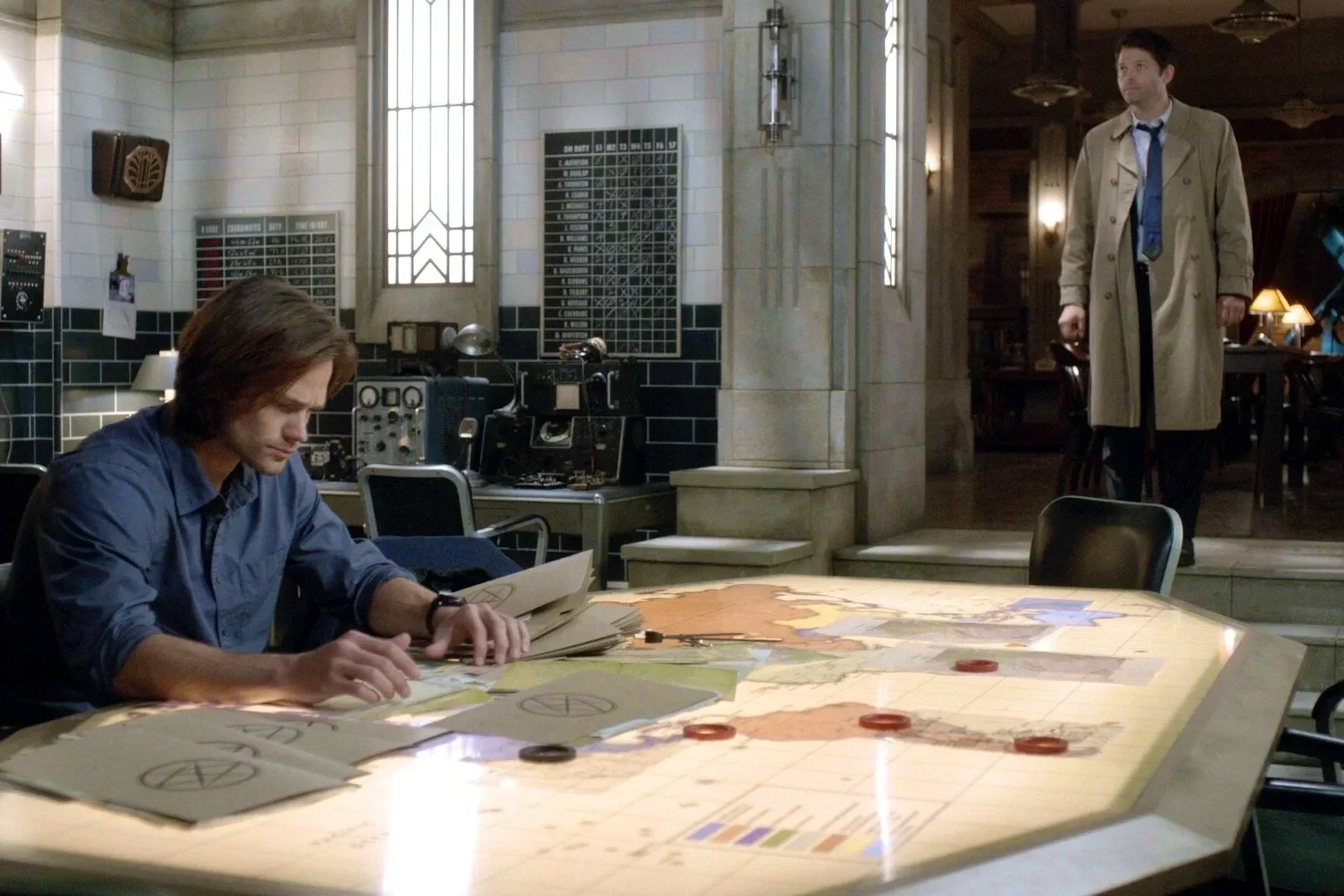

P: The Men of Letters bunker set is so iconic and an essential part of the show. How was the process of designing that?

JW: Looking at the timeline in the show, it matched up with the WPA [Works Progress Administration] movement, a time period around the 1930s where they put a ton of government funds into these wonderful libraries, museums, and power plants. I saw the Men of Letters as these free masons—they were heads of the industry, but they were also scientists and astronomers. So I said, ‘Look, we can go Art Deco with this.’ We’ll make a facade on top of a WPA power plant, and once they go in the door, we can do whatever we want. Everybody’s saying, ‘They’re not going to let you build that’ because it’s a lot of money. But the reasoning was: if we can shoot here for five years, then we’ll have saved a lot of money. Then, every couple episodes, we tore something down and added something. Like the firing range—I’m a big Wes Anderson fan, so it was simple and symmetrical—and Jensen’s man cave, which was replaced by the electric room and then the hospital and so on.

Courtesy of Jerry Wanek

P: You have designed so many miscellaneous ephemera, from motel postcards to magazines. How did you make those minute details with your team?

JW: That’s really my graphics department. Lee Anne, who has a wicked sense of humour, came up with the dance steps for the Hustle in the disco room. We go out on a limb, and then we land on something like the porno mag…

P: Busty Asian Beauties.

JW: Yeah [laughs]. Eric Kripke was a big proponent of ‘Put it out there, and then ask forgiveness.’ And we got a way with a lot. That comes down to just enjoying what you do and feeling like you have the freedom to express yourself, however wacky it is. We spent a lot of time on little details because they weren’t just a throwaway thing. If we made bar coasters, they had to connect to the narrative.

Courtesy of Jerry Wanek

P: Why do you think the show was able to last 15 years?

JW: I remember it was about Season 5, and Eric was leaving. Bob [Singer] and everybody wanted to know what we were going to do, because it’s kind of bad for your career if you stay with one show for that long when you’re a designer. Same thing for our director of photography, Serge Ladouceur. But we said, ‘You know what, this is about legacy now. We have all this creative freedom because we’re travelling all the time. So we’re not stuck in one look.’ We shot in very modern places and in very old places, and we did a Western. So we got to continually challenge ourselves, and it wasn’t like being on a sitcom or a show with a standing set.

And the boys were very special. Not only were they great actors, but they also welcomed all our guest stars. That’s not always the case—a lot of times it becomes a pissing contest, but Jared and Jensen were the exact opposite. They were very generous, and hence we had these incredible guest stars, and a lot of them—who were only scheduled to come in for like an episode—were so beloved that they ended up with us for 10 years. Bobby was with us to the end; Castiel was with us to the end. Then Crowley and Ruth… And we had incredible writers. 15 years of incredible writers. Eric was special. I got to work with James Cameron and John Woo, and Eric is right up there with anybody I've ever worked with. Today, he’s still living proof with The Boys and Jensen's new show [Vought Rising]. And he asked me to work on every show, which is just so cool, you know? But I didn't want to leave Supernatural, so I didn’t do Revolution, Timeless, and The Boys. But we remain close friends. He's one of the first guys I write to when I finish a painting.

Courtesy of Jerry Wanek

P: You directed three episodes of the show. How was the transition from production designer to director?

JW: It was scary as hell. I can come off as a ‘Yeah, I got this’ guy, but inside I’m thinking, ‘Oh, my God, what am I gonna do?’ I was asked early on if I wanted to direct by Bob. I said, ‘I wasn’t ready.’ I even got asked by a Dark Angel producer back in the day. My biggest fear was directing the talent. It wasn’t the technical stuff—it was really about: ‘How do I get a performance out of the actor?’ After he asked me again, instead of just calling Bob, who’s a dear friend, I emailed him so he could say no, and it wouldn’t be personal. In about 10 seconds, he called me and went, ‘What episode do you want?’

As a production designer, I had spent a lot of time at the monitors. You think you know what’s going on… until you sit in the chair! Now I’m not just one of the 200 people around the monitor, I am the monitor. I’m the guy that everybody’s asking questions to. Luckily, everybody was very supportive. That’s another thing, because Misha, Serge, and Richard [Speight Jr., who plays Gabriel] all directed. The crew really liked the fact that it was one of their own who was getting an opportunity.

Courtesy of Jerry Wanek

I had to catch myself a couple times because both Jared and Jensen, the stuff they bring to the table that is not on the page… You don’t realise it until you’re sitting in the chair. Their instincts are just so good. Directing my first episode was hard, but it was like when I first did production design—the adrenaline hit, and I thought, ‘I want more of that.’ Going back to that 22-year-old kid who was working on a McDonald’s commercial, I never thought I’d get that opportunity. Even when I had that opportunity, I was too afraid to take it. When I finally did… Those are some of the best memories of my life. Being in that chair, there’s nothing like it.

P: This might be a hard question, given that you spent 15 years on the show, but which set are you most proud of?

JW: The Men of Letters [bunker]. Because it stood the test of time. We built some really cool churches and bars, but the Men of Letters is quintessential. It was great because Jared and Jensen loved it. There’s a little clip of Jensen on the day they were taking sledgehammers to the Men of Letters. He mentioned that I couldn’t go down there and watch because it was just too hard.

Courtesy of Jerry Wanek

It enabled them to stay with the show a lot longer because our shooting schedules got better. The set meant they could take more time off to be with family. Everybody was getting a little tired—because it’s a grind. Now we could shoot multiple scenes in one day, in one place. I’m so grateful to them for staying with the show for 15 years. They could have left after five. They stuck around because it was a great job, but it was also because we had a family. They’re part of the family to this day. They just did a convention in Vancouver, and I was invited to do the panel, but I’m trying to get some paintings done that we’re going to start auctioning off for Misha’s charity. I’m going to Nashville over Halloween, so I still see everybody.

The conventions are crazy—they’re more popular now than they were when we were doing the show! It's the 20th anniversary, and people are really embracing it. You know, my friend Tedra [Ashley-Wannemuehler], she’s an artist, and she found her partner at a convention. She had sent me a little maquette of one of my motel rooms, and my assistant at the time, Susie, showed it to me. I went, ‘Wow, give me her information because I want to meet her.’ You can’t do that with many, but now we’re close friends. I mean, I probably text her once a week. There’s this whole culture of people meeting at our conventions, and like your magazine, there are a lot of outsiders. There are a lot of people who don’t fit the mould, but they have this commonality. That’s better than anything we could have ever imagined. The opportunity for people to connect, especially in this climate, when they’re so marginalised, is really special. .

20 Years of Supernatural: Looking Back on the Road So Far with Jerry Wanek

The production designer, co-producer, and director reflects on the record-breaking horror series

by Lana Thorn 18 December 2025 Extended interview originally published in Issue 004

Courtesy of Jerry Wanek

Over 15 years and 327 episodes, Sam and Dean Winchester saved people and hunted things across the United States. Driving in a black 1967 Chevrolet Impala, they stopped by Heaven, Hell, and nearly 200 motel rooms—and practically every detail in those many sets, from wallpaper postcards, was designed by Jerry Wanek.

Along with his art department, week after week, Wanek transported viewers into the world of Supernatural. Aside from the blend of horror, rock music, and brotherly banter, the cult series is known for its Americana aesthetic. But as die-hard fans will tell you, the CW series was shot almost entirely in Vancouver, with Wanek meticulously crafting each diner, billboard, and gas station to deceive the audience.

Supernatural concluded in 2020, making it the longest-running genre show in US television history. Five years and a few TV shows later, the 71-year-old production designer calls me over Zoom from his home in Jupiter, Florida. Taking a break from his painting (he’s contributing pieces to SPN actor Misha Collins’ charity, Random Acts), Wanek discusses his favourite motel room, how Jensen Ackles made him ditch Criminal Minds to join the show, and why Supernatural is more popular now than ever.

Wanek on a set from Season 15, Episode 19, “Inherit the Earth”

Lana Thorn: Before we dive into Supernatural, I wanted to ask: Do you have an early memory of realising you were a creative person?

Jerry Wanek: I grew up in a big family in Wisconsin, and I definitely didn’t fit in. I was off the rails—if it had been today, I would have been on everything: Ritalin, Adderall… Nobody from our small town was an artist, and my dad was very pragmatic. He built houses, and he did some designing when it was called for. Some of my earliest recollections are sitting across from him when he was drawing blueprints, and I would have a piece of paper and try to emulate that.

P: How did you get into the film industry?

JW: After I moved to LA, I managed a bar, and when people in the film business came in, I would beg them for a job. One day, there was a fire at this production house, and they needed somebody to clean it up. I said, ‘I’ll do it!’ They had this big McDonald’s commercial coming up, and they said, ‘Well, if Jerry’s willing to clean up that crap after the fire, let’s give him a shot.’ And that was my first job: getting Ronald McDonald coffee—and Heineken. I worked my way up to first assistant director, but I was always gravitating towards the art department.

Courtesy of Jerry Wanek

P: How did you end up as a production designer?

JW: I worked with an amazing production designer named Vance Lorenzini, who did the Madonna ‘Express Yourself’ video. There was a lot of creative freedom in doing music videos: we did these huge sets. Then I worked with Tim Newman, this fantastic director who did all the ZZ Top videos—and ZZ Top ruled original MTV. It was “Viva Las Vegas”, and his production designer—whom I was working with—wasn’t available. Next thing I knew, I was on a plane to Las Vegas. I didn’t sleep. It was the hardest thing I've ever done. But now I had the creative freedom again, and I just thought, ‘I need more of that.’

I established myself, but when you’re doing music videos and commercials, you can’t do film or TV because you haven’t done it yet. It’s these catch-22s. Then Kenny Rogers gave me a shot with The Gambler, and all of a sudden, I was the Western guy. Even though I always liked more modern, minimalist stuff. I did several Westerns with Larry McMurtry (who wrote The Last Picture Show and Brokeback Mountain), and the textures, the different colours and layers in those films—I can see it now in everything I do. I liked the depth and the age. When we do a set, nothing can be new. I never really wanted to do TV, but once I did The Magnificent Seven, I was working on something for 10 months rather than spending a week on a commercial. I got to tell a story, and that’s the most important thing about designing.

Jensen Ackles in Dark Angel. Courtesy of Jerry Wanek

P: What was the transition like from working on those Westerns to a sci-fi show like Dark Angel?

JW: That was tough. Mark Freeborn—who’s a brilliant designer, he did Breaking Bad and some of The X-Files—had done the pilot, but he didn’t want to do the show. I think he was fed up with [James] Cameron and Fox at the time. When Cameron okayed me, my agent said, ‘You know, he likes to fire production designers.’ But it turned out really well. He came up and directed the last episode, and that opened my eyes. A lot of people like to badmouth Cameron, but you work alongside him, and you’re in awe. No one works harder; no one is more focused. I’ve never seen anybody as intelligent in any subject matter.

P: How did you get involved in Supernatural, and what attracted you to the series?

JW: I had just done the pilot for Criminal Minds when I got a call from my agent. He goes, ‘There’s a show up in Vancouver that Jensen Ackles is gonna be on.’ And I said, ‘I’ll take it.’ I didn’t know the name; I didn't know anything. But my experience watching him on Dark Angel was that he stole every scene. He was so charismatic, and he was such a good actor, that I was thinking, ‘This is the guy you want to hook your wagon to.’ That was the smartest move I ever made. I’m not that big a fan of horror and gore, but I got to use all the things that I love about set design: textures, colours, and layers. I wanted to do cool, creepy places and abandoned churches, and we built almost all of those sets.

The thing about Supernatural is, you can't go into somebody’s house—even if you find a house big enough to shoot in—because you throw people through the walls or splatter blood. It got to a point, halfway through the first year, where [creator Eric] Kripke said, ‘We’ll just build it.’ They’d say, ‘Let Jerry and the art department figure something out.’ That was fun, and also more pressure, but it was great.

Courtesy of Jerry Wanek

P: What is something that you find to be misunderstood about the role of a production designer?

JW: No one knows what it is! They really don’t know. It goes like this, ‘Oh, you’re a production designer.’ ‘Yeah, I oversee the look of the film.’ ‘Oh, so you design sets?’ ‘Well, that’s part of it, but really, I oversee eight set designers and props…’ The biggest thing I tell PDs who worked under me is: ‘Just tell the story.’ You know Bob Singer, who was the showrunner and captained the ship for all 15 years of Supernatural, that was his mantra. When I got the opportunity to direct and was crazy nervous, that’s what he told me: ‘Just tell the story.’ Because it’s tempting to do something wild, but if it has nothing to do with the story, you haven’t done your job.

Courtesy of Jerry Wanek

P: Early on, Warner Bros. was considering a deal with Motel 6. Why did you push back on the deal and fight to design the motel rooms yourself?

JW: Episode 2 or 3, they said, ‘We’re going to make a deal and build one motel room, so wherever you go, you can have a standing set.’ I said, ‘Well, you can do that. But you’re gonna need a different art department.’ Because this was the only way of telling the audience where we were, to give them a sense of place. We always wanted the motel rooms to have something to do with the city or the state. Even today, when I talk to people, they say, ‘Wow, you went all over the place.’ I go, ‘We never left Vancouver!’

Courtesy of Jerry Wanek

I remember the first room we did—I love quirky Americana, and I thought, ‘This is gonna be cool.’ And what I do most of the time is open the set. I’m there the first time the crew comes in, and later when the cast comes in. So I’m sitting in the background, and Jared and Jensen walk in, but they just start doing their blocking, never looking around [to appreciate the set]. I said, ‘Okay, we’re gonna fix that.’ We just kept pushing it and pushing it, and we had so much fun. I remember after only Season 1, after 15 motel rooms, we thought, ‘We’re gonna run out of ideas.’ We ended up doing 173.

In terms of quirkiness, the most famous one in Season 1 was the disco motel. I hadn’t told Phil Sgriccia, who’s a great director and a good friend, what I was doing. He opens the door before the cast gets there, and he goes, ‘Holy cow! ’ So he says, ‘Now I have to put a camera inside, and when the boys open it, we can get a visceral reaction.’ And they did have one. They immediately started disco dancing, and next thing you know, they’re jumping and dancing on the beds. But if you look at that motel room and pick it apart, everything in there has a purpose, including the dance steps to the Hustle, which are on the back of the door. So if you’re gonna go all out, you gotta support it. And everybody got on board. My decorator, George Neuman, and my graphic artists, who are the best on the planet: Lee Anne [Elaschuk], Mary Ann [Liu], and Eric [Jorgensen].

© Warner Bros.

P: Do you have a favourite motel?

JW: There are probably a dozen. I like a lot of the more kitschy ones—the Route 66 one with the mudflap girls. The disco one is certainly up there… But there are so many of them, and everybody had a say in them. The way I run my art department, I never had an office—it was a bullpen. So I could hear everybody, and the best idea wins. My philosophy was that these people were all very accomplished artists. We’d get a nice bottle of wine, and whoever had the best idea of the week would get the wine. It really helped with our look, especially with sustaining for as long as we did. So basically, I stole all their ideas and said they were mine.

Courtesy of Jerry Wanek

P: The Men of Letters bunker set is so iconic and an essential part of the show. How was the process of designing that?

JW: Looking at the timeline in the show, it matched up with the WPA [Works Progress Administration] movement, a time period around the 1930s where they put a ton of government funds into these wonderful libraries, museums, and power plants. I saw the Men of Letters as these free masons—they were heads of the industry, but they were also scientists and astronomers. So I said, ‘Look, we can go Art Deco with this.’ We’ll make a facade on top of a WPA power plant, and once they go in the door, we can do whatever we want. Everybody’s saying, ‘They’re not going to let you build that’ because it’s a lot of money. But the reasoning was: if we can shoot here for five years, then we’ll have saved a lot of money. Then, every couple episodes, we tore something down and added something. Like the firing range—I’m a big Wes Anderson fan, so it was simple and symmetrical—and Jensen’s man cave, which was replaced by the electric room and then the hospital and so on.

Courtesy of Jerry Wanek

P: You have designed so many miscellaneous ephemera, from motel postcards to magazines. How did you make those minute details with your team?

JW: That’s really my graphics department. Lee Anne, who has a wicked sense of humour, came up with the dance steps for the Hustle in the disco room. We go out on a limb, and then we land on something like the porno mag…

P: Busty Asian Beauties.

JW: Yeah [laughs]. Eric Kripke was a big proponent of ‘Put it out there, and then ask forgiveness.’ And we got a way with a lot. That comes down to just enjoying what you do and feeling like you have the freedom to express yourself, however wacky it is. We spent a lot of time on little details because they weren’t just a throwaway thing. If we made bar coasters, they had to connect to the narrative.

Courtesy of Jerry Wanek

P: Why do you think the show was able to last 15 years?

JW: I remember it was about Season 5, and Eric was leaving. Bob [Singer] and everybody wanted to know what we were going to do, because it’s kind of bad for your career if you stay with one show for that long when you’re a designer. Same thing for our director of photography, Serge Ladouceur. But we said, ‘You know what, this is about legacy now. We have all this creative freedom because we’re travelling all the time. So we’re not stuck in one look.’ We shot in very modern places and in very old places, and we did a Western. So we got to continually challenge ourselves, and it wasn’t like being on a sitcom or a show with a standing set.

And the boys were very special. Not only were they great actors, but they also welcomed all our guest stars. That’s not always the case—a lot of times it becomes a pissing contest, but Jared and Jensen were the exact opposite. They were very generous, and hence we had these incredible guest stars, and a lot of them—who were only scheduled to come in for like an episode—were so beloved that they ended up with us for 10 years. Bobby was with us to the end; Castiel was with us to the end. Then Crowley and Ruth… And we had incredible writers. 15 years of incredible writers. Eric was special. I got to work with James Cameron and John Woo, and Eric is right up there with anybody I've ever worked with. Today, he’s still living proof with The Boys and Jensen's new show [Vought Rising]. And he asked me to work on every show, which is just so cool, you know? But I didn't want to leave Supernatural, so I didn’t do Revolution, Timeless, and The Boys. But we remain close friends. He's one of the first guys I write to when I finish a painting.

Courtesy of Jerry Wanek

P: You directed three episodes of the show. How was the transition from production designer to director?

JW: It was scary as hell. I can come off as a ‘Yeah, I got this’ guy, but inside I’m thinking, ‘Oh, my God, what am I gonna do?’ I was asked early on if I wanted to direct by Bob. I said, ‘I wasn’t ready.’ I even got asked by a Dark Angel producer back in the day. My biggest fear was directing the talent. It wasn’t the technical stuff—it was really about: ‘How do I get a performance out of the actor?’ After he asked me again, instead of just calling Bob, who’s a dear friend, I emailed him so he could say no, and it wouldn’t be personal. In about 10 seconds, he called me and went, ‘What episode do you want?’

As a production designer, I had spent a lot of time at the monitors. You think you know what’s going on… until you sit in the chair! Now I’m not just one of the 200 people around the monitor, I am the monitor. I’m the guy that everybody’s asking questions to. Luckily, everybody was very supportive. That’s another thing, because Misha, Serge, and Richard [Speight Jr., who plays Gabriel] all directed. The crew really liked the fact that it was one of their own who was getting an opportunity.

Courtesy of Jerry Wanek

I had to catch myself a couple times because both Jared and Jensen, the stuff they bring to the table that is not on the page… You don’t realise it until you’re sitting in the chair. Their instincts are just so good. Directing my first episode was hard, but it was like when I first did production design—the adrenaline hit, and I thought, ‘I want more of that.’ Going back to that 22-year-old kid who was working on a McDonald’s commercial, I never thought I’d get that opportunity. Even when I had that opportunity, I was too afraid to take it. When I finally did… Those are some of the best memories of my life. Being in that chair, there’s nothing like it.

P: This might be a hard question, given that you spent 15 years on the show, but which set are you most proud of?

JW: The Men of Letters [bunker]. Because it stood the test of time. We built some really cool churches and bars, but the Men of Letters is quintessential. It was great because Jared and Jensen loved it. There’s a little clip of Jensen on the day they were taking sledgehammers to the Men of Letters. He mentioned that I couldn’t go down there and watch because it was just too hard.

Courtesy of Jerry Wanek

It enabled them to stay with the show a lot longer because our shooting schedules got better. The set meant they could take more time off to be with family. Everybody was getting a little tired—because it’s a grind. Now we could shoot multiple scenes in one day, in one place. I’m so grateful to them for staying with the show for 15 years. They could have left after five. They stuck around because it was a great job, but it was also because we had a family. They’re part of the family to this day. They just did a convention in Vancouver, and I was invited to do the panel, but I’m trying to get some paintings done that we’re going to start auctioning off for Misha’s charity. I’m going to Nashville over Halloween, so I still see everybody.

The conventions are crazy—they’re more popular now than they were when we were doing the show! It's the 20th anniversary, and people are really embracing it. You know, my friend Tedra [Ashley-Wannemuehler], she’s an artist, and she found her partner at a convention. She had sent me a little maquette of one of my motel rooms, and my assistant at the time, Susie, showed it to me. I went, ‘Wow, give me her information because I want to meet her.’ You can’t do that with many, but now we’re close friends. I mean, I probably text her once a week. There’s this whole culture of people meeting at our conventions, and like your magazine, there are a lot of outsiders. There are a lot of people who don’t fit the mould, but they have this commonality. That’s better than anything we could have ever imagined. The opportunity for people to connect, especially in this climate, when they’re so marginalised, is really special. .